The 2 most important Finals questions heading to Game 3

The Dallas Mavericks are heading home in a 2-0 hole in the NBA Finals, having trailed the Boston Celtics for all but 30 seconds in the combined second halves of Games 1 and 2. As the series shifts to Dallas, let’s dig into the key factors that contributed to Boston’s decisive victories by posing two questions that will determine whether the Mavericks can turn things around.

Can the Mavs crack the Celtics’ defensive code?

As much as Dallas rode its improved defense to the Finals, this is a team that relies heavily on an offense driven by two of the sport’s most dynamic creators. Through two Finals games, that offense has been bottled up by Boston’s airtight defense, limited to an even 100 points per 100 possessions.

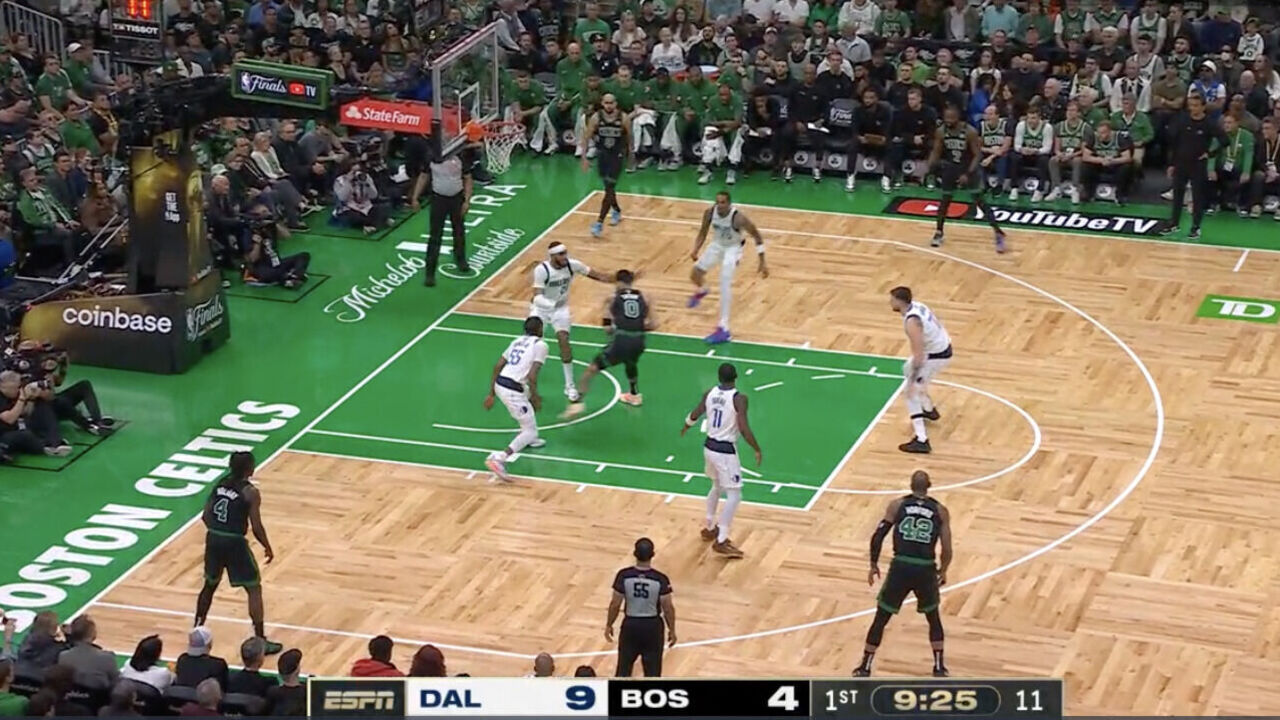

As expected, the Celtics have scrambled the Mavs’ preferred pick-and-roll actions by guarding Dallas’ centers with smalls (most often Jayson Tatum) while cross-matching their own centers onto low-usage wings (most often Derrick Jones Jr.). That’s turned every ball screen from Daniel Gafford or Dereck Lively II into an automatic switch that puts Tatum on Luka Doncic or Kyrie Irving while the beefier Jaylen Brown comfortably shifts to center duty.

Coupled with Boston’s size on the back line, that liberal switching has taken away much of the north-south momentum the Mavs’ pick-and-rolls typically generate and made their offense extremely stationary. Those Dallas bigs have seen their rim-running opportunities dry up, which is why Lively has just four points in the series.

The Celtics have avoided sending hard double-teams at Doncic regardless of matchup or screen defender, but they’ve shown aggressive nail help off of the Mavs’ so-so shooters (Jones, P.J. Washington, Josh Green, et. al) to curtail his drives. And while Doncic has done a solid job of scoring in isolation against the variety of defenders being thrown at him via primary assignments and switches, he hasn’t been dominant enough to make the Celtics rethink their approach, even when it’s Al Horford switching onto him.

Irving, meanwhile, has scored 28 points on 38 shooting possessions with eight assists against five turnovers in the two games. He’s mostly been hounded by Jrue Holiday, who’s often made it a point not to switch but to fight through screens instead.

In declining to put two on the ball, the Celtics have also taken away Dallas’ skip passes and 4-on-3 kickouts. The Mavs came into the Finals averaging 11.6 corner 3-point attempts per game, but in the first two contests of this series, they’ve attempted eight total, hitting two. They haven’t even won the offensive rebounding battle despite seeing a wing or guard boxing out their center on nearly every possession.

All that said, things aren’t yet hopeless for Dallas. The team had a better offensive showing in Game 2, thanks in part to a couple of adjustments.

After finding minimal success turning Jones into a high-volume ball-screener to pull Boston’s bigs into the action, Doncic decided he was more comfortable playing pick-and-roll with his centers and simply attacking the Tatum switch, which he did pretty effectively. He and Irving also made a point of looking for Gafford on the back end of those switches, which produced surprisingly good results.

When the Mavs did use Jones as a screener in Game 2, they were more considerate in where they had him screen and how they spaced the floor around him, so he wasn’t just rolling into traffic or popping above the break (where no defender ever follows him). He got his only lob dunk of the series by screening for Doncic near midcourt and then diving toward an empty side. He got a rolling layup when the Mavs ran a Spain pick-and-roll, freeing him up by mashing the trailing switch defender with a back screen. They used him as an off-ball screener more frequently to try to generate action on the weak side that would make it harder for Boston’s bigs to lay back.

Dallas also moved Doncic off the ball a bit more to alleviate some pressure and try to create some easier looks for him, and he responded by moving around in a way he rarely does. He zipped up off of pindowns, cut backdoor, and even hit an ultra-rare catch-and-shoot corner three coming off a cross screen under the basket. Having Payton Pritchard’s man screen for him off-ball worked to force one of the few switches Boston can’t feel totally comfortable with. Dallas also toyed with playing Maxi Kleber at center to try and open up the floor, a look that went plus-8 in seven minutes despite Kleber being either unable or unwilling to shoot due to his injured shoulder.

All told, the Mavs shot 18-for-22 at the rim and a respectable 14-for-32 on non-rim 2-pointers in Game 2. The problem was that they got up just 26 threes and hit only six, missed eight free throws, and turned the ball over 15 times. That last bit was uncharacteristic not only for their offense, which is one of the best in the league at ball protection, but for Boston’s defense, which ranked dead last in opponent turnover rate this season. Doncic accounted for eight of those turnovers, and a lot of them were just sloppy miscues that can be cleaned up. The simplest and most obvious fix to all of this would be getting more out of Irving, who is certainly capable of scoring more efficiently even with Holiday and Derrick White dogging him.

Does all of that represent enough upward mobility to make you believe Dallas can flip this series? Even if you bake in some positive 3-point regression, you have to do the same for Boston, which shot just 10-for-39 from deep in Game 2. Even when the Mavs inevitably shoot better at home, it’ll still be an issue if they keep generating way fewer attempts from beyond the arc than the Celtics are, especially if they keep losing the rim battle.

Speaking of which …

Will Boston remain committed to the drive?

One of the nitpicks about the Celtics this season – and nits are all you can pick from a 64-18 team with a top-10 all-time margin of victory – has been that they shoot too many threes and don’t go to the rim enough. But they just won a Finals game in which they shot 26% from 3-point range, and they did so not only because of their defense but because of their commitment to driving the ball.

Drives on their own don’t necessarily correlate to good offense – Boston ranked 28th in that category during the regular season and still produced more points per possession than any team in NBA history – but they’ve been instrumental in countering Dallas’ switch-happy, paint-collapsing defense. The Mavs are trying to defend like the Celtics by switching almost everything up top and bringing help later, but they’re obviously not as equipped to deal with the resulting matchups. They’re trying to bait Tatum and Brown into taking meandering mid-rangers in isolation, but Tatum and Brown aren’t taking the bait. Instead, they’re attacking with decisiveness, speed, and blunt force.

They’ve particularly enjoyed hunting Doncic and roasting him off the bounce. They’re also picking on the smaller Irving, bully-driving him into the post and forcing help. The Mavs are switching their big men out, too, but rather than settling for step-back threes against that matchup, Boston’s lead ball-handlers are taking advantage of their speed advantage and the fact that Dallas is willingly pulling its best rim-protectors away from the basket.

The Celtics have shot 83% inside the restricted area in the series (Dallas came in allowing 59% for the playoffs), and that interior scoring proficiency doesn’t come close to capturing the pressure they’ve put on the rim. They drove 66 times in Game 2 after coming into the series having averaged 40.9 drives per game in the playoffs and 39.1 during the regular season, per NBA Advanced Stats. Tatum led the charge with an astonishing 29 of those drives in Game 2 after rumbling for a team-high 18 in Game 1. Brown came in right behind him with 23 and 14 in the two contests.

All season the Celtics’ offense has been engineered to play drive-and-kick, but their two lead creators have rarely driven or kicked quite like this. So far in the Finals, they’ve more than doubled their collective drives from the regular season. And thanks to the amount of help Dallas is sending at those drives, the two of them are passing out at a significantly higher rate than they’re accustomed to doing.

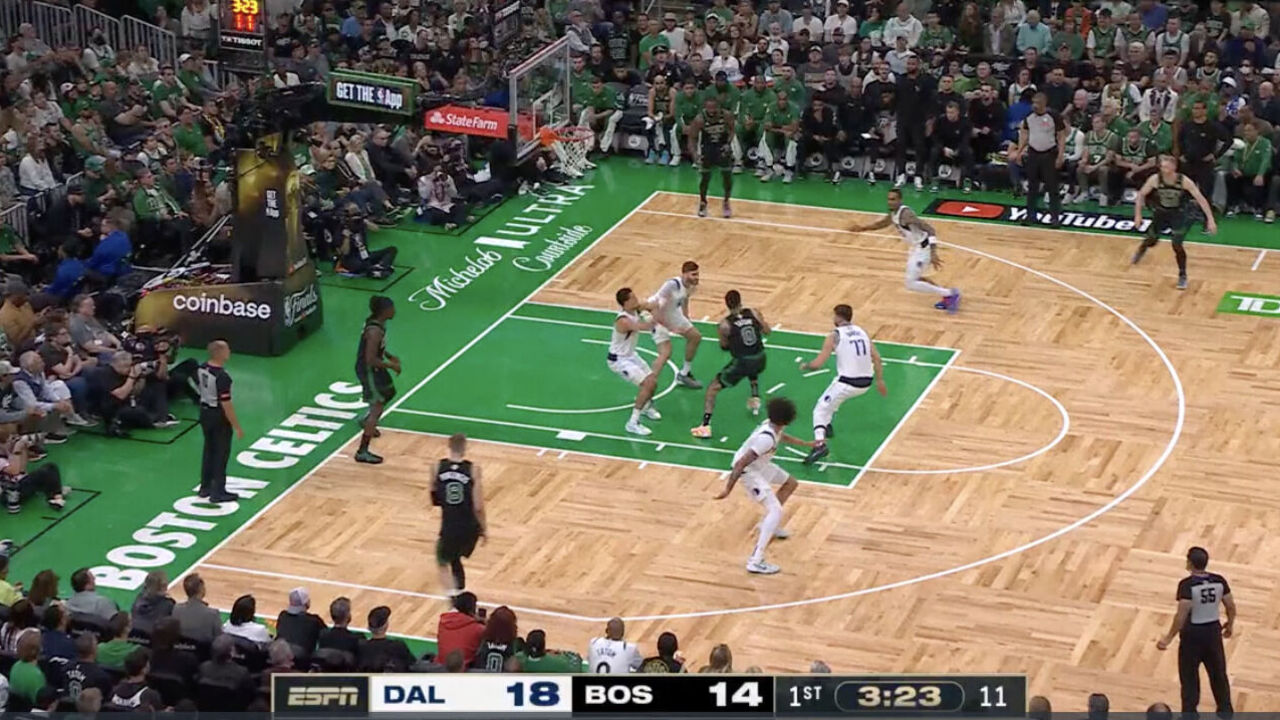

The Mavs turned their defense around in large part by prioritizing the interior, but the Celtics are using that mandate against them. You can see the buffet of passing options available to them once the defense converges on the paint:

There are kickouts to the perimeter, laydowns to the various guards Boston is stationing in the dunker spot, and lanes for backdoor cuts. Holiday in particular exploited those off-ball scoring avenues in Game 2.

Tatum and Brown usually drive to score, but now they’re driving with the intention of creating a defensive reaction that will lead to a great scoring chance for someone else. Their 19 combined assists in Game 2 were the most they’ve ever racked up in a playoff game. Boston is averaging 30 catch-and-shoot 3-point attempts per game, compared to just 14 for Dallas.

Some defensive tweaks might help the Mavs, starting with making more of an effort to keep their big men on the back line, especially when the dunker spot is occupied. They could then ease up a bit on the supplemental help and challenge the Celtics’ drivers to finish over length at the rim. But that won’t matter much if they can’t do a better job of containing dribble penetration. Specifically, if they’re committed to switching the way they did in Games 1 and 2, Doncic needs to do a better job of keeping the ball in front, which may be tough to do considering he appears to be playing through multiple injuries.

Statistically speaking, the Mavs’ defense hasn’t been their problem; they’ve held the Celtics’ offense nearly seven points per 100 possessions below its postseason average. But from a process standpoint, there’s a lot to be concerned about. If they keep defending the way they have been and Boston remains committed to driving in response, this could be a short series.

Joe Wolfond covers the NBA for theScore.