Sports boomed, reflected America, and changed forever in the 1970s

Apps like theScore didn’t exist when Michael MacCambridge grew up in Kansas City in the 1970s, back when it was harder for a kid to follow the hometown team. Late Royals games that ran past his bedtime sometimes ended after the morning newspaper went to print. The sports section relayed who led through seven innings.

The suspense dogged MacCambridge, now an author of sports history books, as he left for grade school.

“Only when I came home and got the afternoon paper could I find out the final score of the game that had been played nearly 24 hours ago,” MacCambridge said. “That is what’s so hard to explain to modern sports fans: What a wasteland it was. Maybe you could get lucky and get a final on the radio. But it was a challenge.”

MacCambridge lived through a transformation. Everything about sports changed in the ’70s. The debut of “Monday Night Football” popularized nighttime broadcasts and helped condition a national audience to crave round-the-clock coverage. The creation of free agency and rogue leagues empowered and enriched players. Gains were made that promoted racial integration and women’s inclusivity.

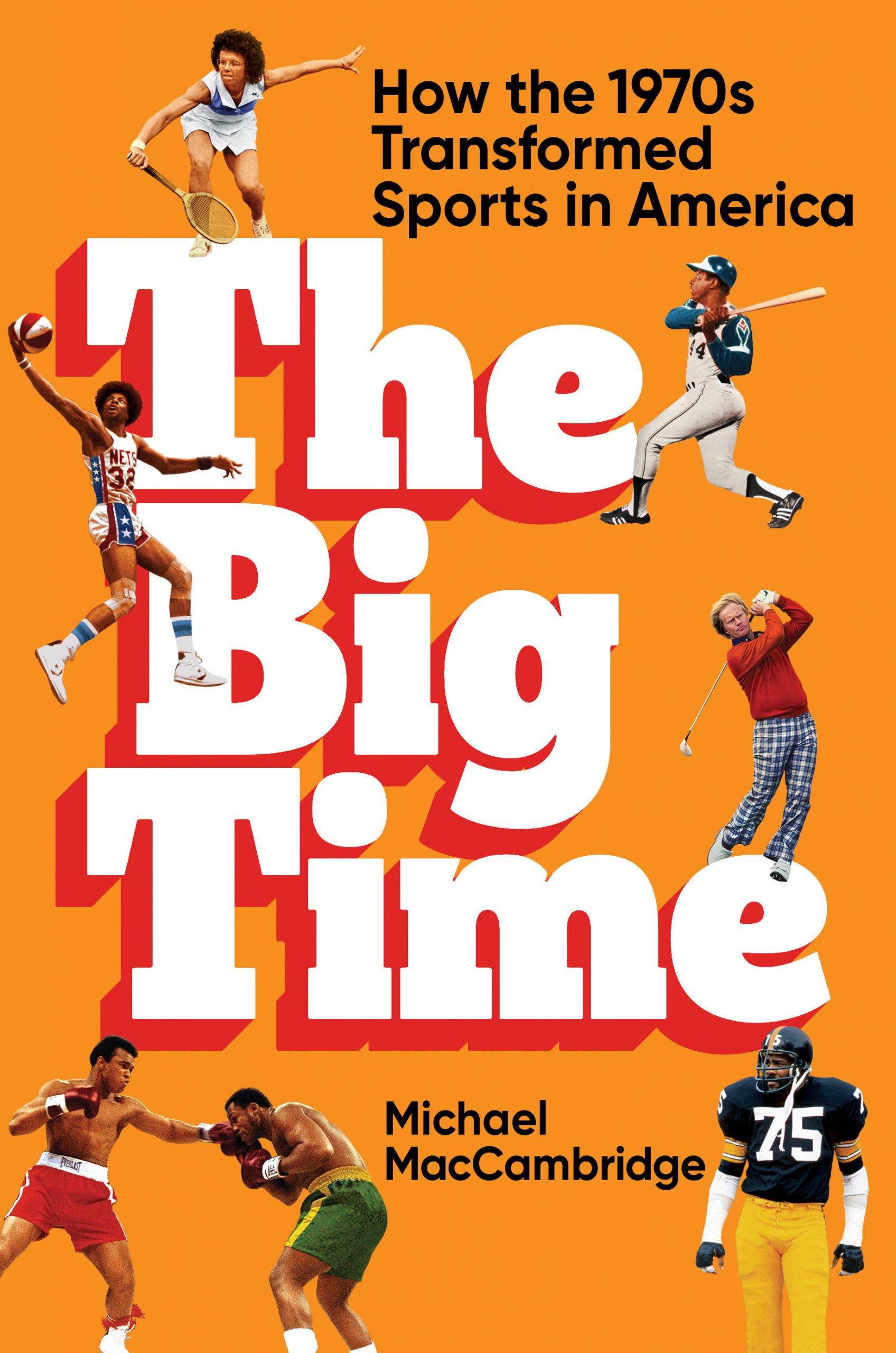

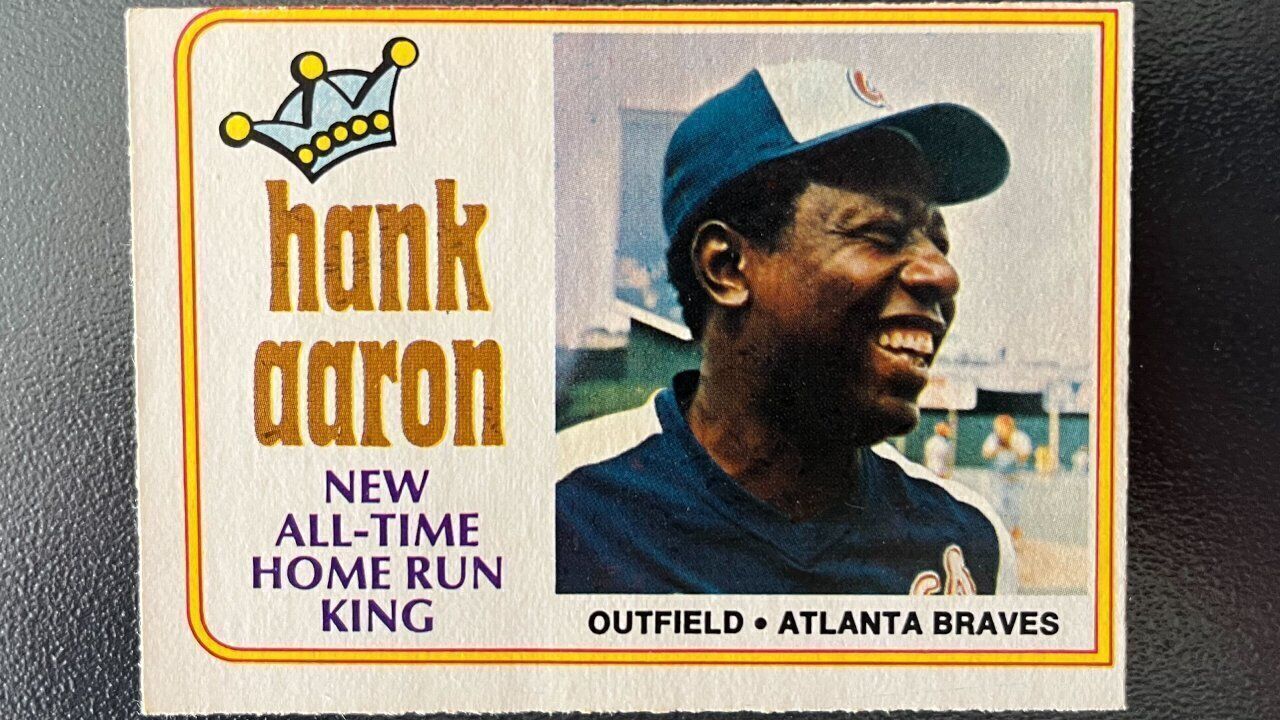

The decade’s innovations and iconic athletes, from Hank Aaron to Kareem Abdul-Jabbar to Muhammad Ali, inspired MacCambridge’s latest work: “The Big Time: How the 1970s Transformed Sports in America,” which was published this week. Every era sparks change, but this rollicking period is when the games we love became a cultural phenomenon, commercial juggernaut, and 24-7 obsession.

Before his book launched, MacCambridge spoke to theScore about the decade’s key characters, indelible sights, and lasting effects.

“By the end of the ’70s, you could see the broad contours of what sports has become today, which is this multimedia, pervasive common ground that has insinuated itself into all the different parts of American life,” MacCambridge said.

“At a time when America is more balkanized, narrowcast, and divided than ever before, sports is the last really big tent. You could start seeing that happen by the end of the ’70s in a way that didn’t exist at the beginning of the ’70s.”

This conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

theScore: How did you experience sports in the 1970s?

MacCambridge: I was 7 years old when the decade began. Fans tend to romanticize sports when they were growing up and falling in love with sports. Your sense of wonder is activated in that decade. I wanted to take a step back from my own emotional experience and try to understand the larger themes.

Growing up in Kansas City, I lived in an apartment complex. There were players from the Chiefs who lived in my building and the next building over. It was an era when players lived in apartment buildings instead of owning them. The Chiefs’ offices were about 10 minutes away in the middle of a park area. There were only about 10 people working there and a practice field out back.

Sports were much less corporate, much less sophisticated, and the stakes were a lot lower then because players were being paid a lot less money. Sports was something different by the time we got to the end of the ’70s.

How did the ’70s legitimize sports fandom? What happened that enabled millions of people to obsess over them?

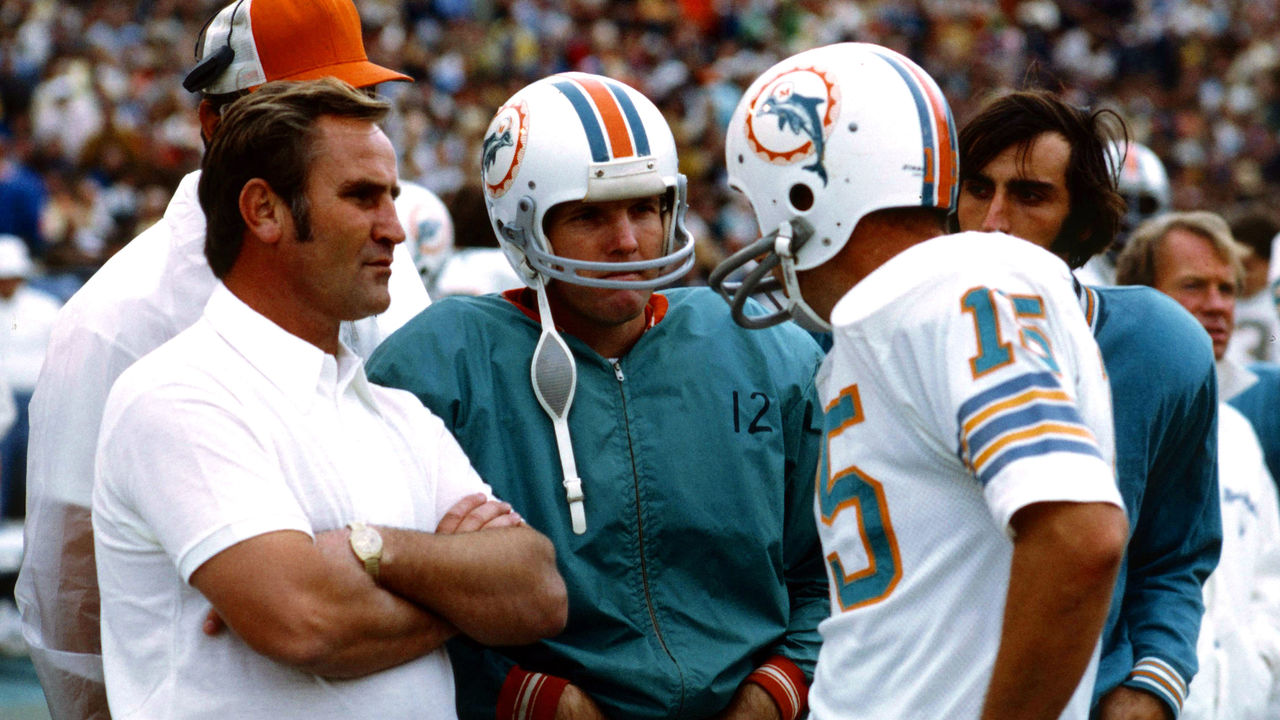

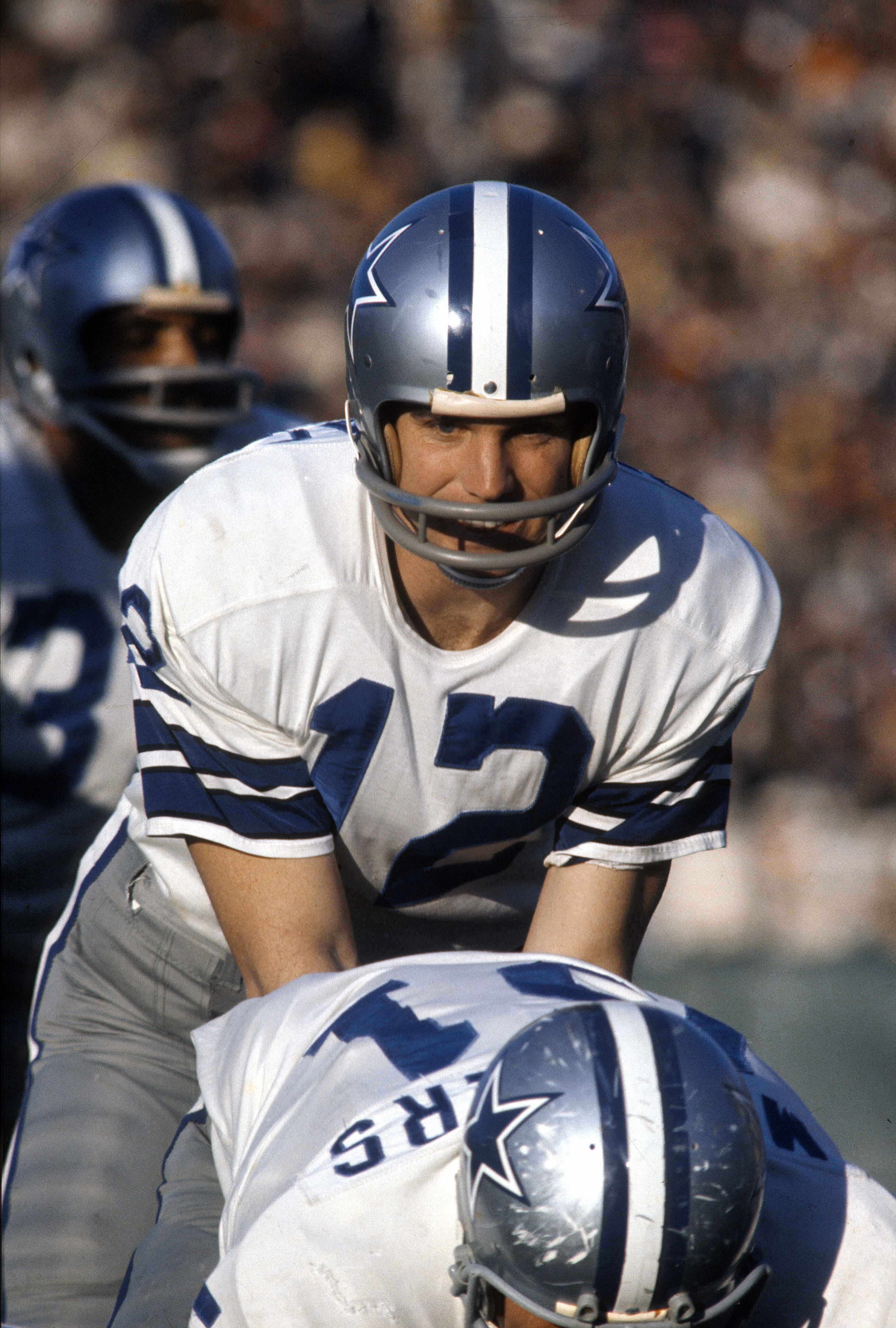

You have to go back to the assumptions that were made at the beginning of the ’70s. There was still a feeling that pro football – which, by then, was America’s most popular sport – was too male, too marginal, too parochial to succeed on prime-time network television. But with the advent and success of “Monday Night Football,” that showed there was a broad audience.

It’s not a coincidence that in 1971, a year after “Monday Night Football” debuts, we have the first World Series game in prime time. In ’72, the Olympics goes to every night in prime time. In ’73, the NCAA has the first national championship game in prime time. “Monday Night Football” opened the door.

Fans had been so regional in their interests and awareness. As more sports were on TV, as more sports pages became national in their outlook, fans were more national. By the time you get to the ’80s and the launch of ESPN, fans are able to follow the games in a way they couldn’t (in the past).

The decade’s top athletes included tennis legend Billie Jean King. She beat Bobby Riggs, the chauvinistic retired major champion, in straight sets in the 1973 “Battle of the Sexes” as 45 million viewers tuned in. As you note in the book, it’s possible no athlete ever delivered under so much pressure. What did her victory mean to some of the women you interviewed?

The match was played in Houston, of course. There was a big viewing party in New York City. It gathered a lot of the women who were at the forefront of second-wave feminism. A lot of them weren’t sports fans, but they knew this was a moment. There’s a scene in the book with the actress Marlo Thomas, who starred in the TV series “That Girl,” sitting in front of the TV and saying this was the most important moment of her life.

Talking to women coaches, athletes, and administrators, it was clear that across the country that night, there was this thing. It was a circus, and there was nothing tangible improved by it one way or the other. Billie Jean King would have been the first to say that she could not have beaten one of the top 100 male players at the time. But because that match had gotten so much attention and had broad societal resonance, it felt huge.

King would have known going into the match that if she lost, that’s what she was going to be remembered for – just as that is what Bobby Riggs is remembered for today, 50 years later.

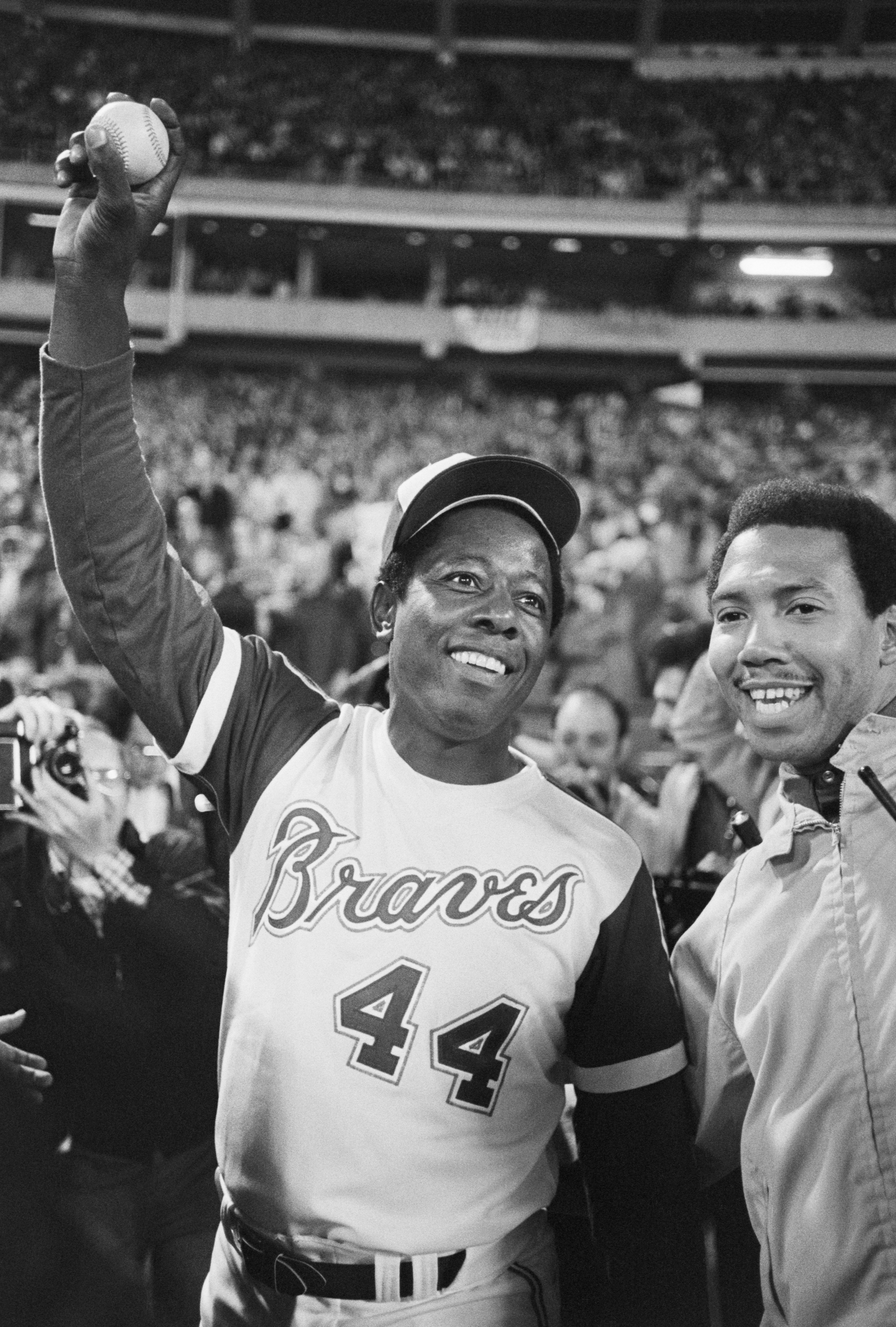

Hank Aaron hit his 715th home run in 1974. He got death threats and racist hate mail while pursuing Babe Ruth, then was celebrated for breaking the record. What did Aaron’s chase signify about that time in American life?

It was important for Aaron to step up and share with the public the nature of the hate mail he received. I think it showed people a side of the country that a lot of middle-class, white sports fans hoped did not exist. It was a reminder that it did exist.

It put a mirror in front of the American sporting public, which tended to congratulate itself for its open-mindedness, for its embrace of Black athletes. It showed how many people were virulently racist, threatening, and dangerous.

The stress of that was clearly immense. I’m not sure another athlete who didn’t have Aaron’s character would have weathered that so well. But he did it. I quote from a biography of Aaron. (Braves teammate) Dusty Baker said, “Hank was a little bit like your dad.” He didn’t bring his problems home to you. You knew he had adult problems, but he didn’t dwell on them.

It was the single most-known record in American sports. Even someone who didn’t follow sports knew Babe Ruth hit 714 home runs. That was what made it so historic.

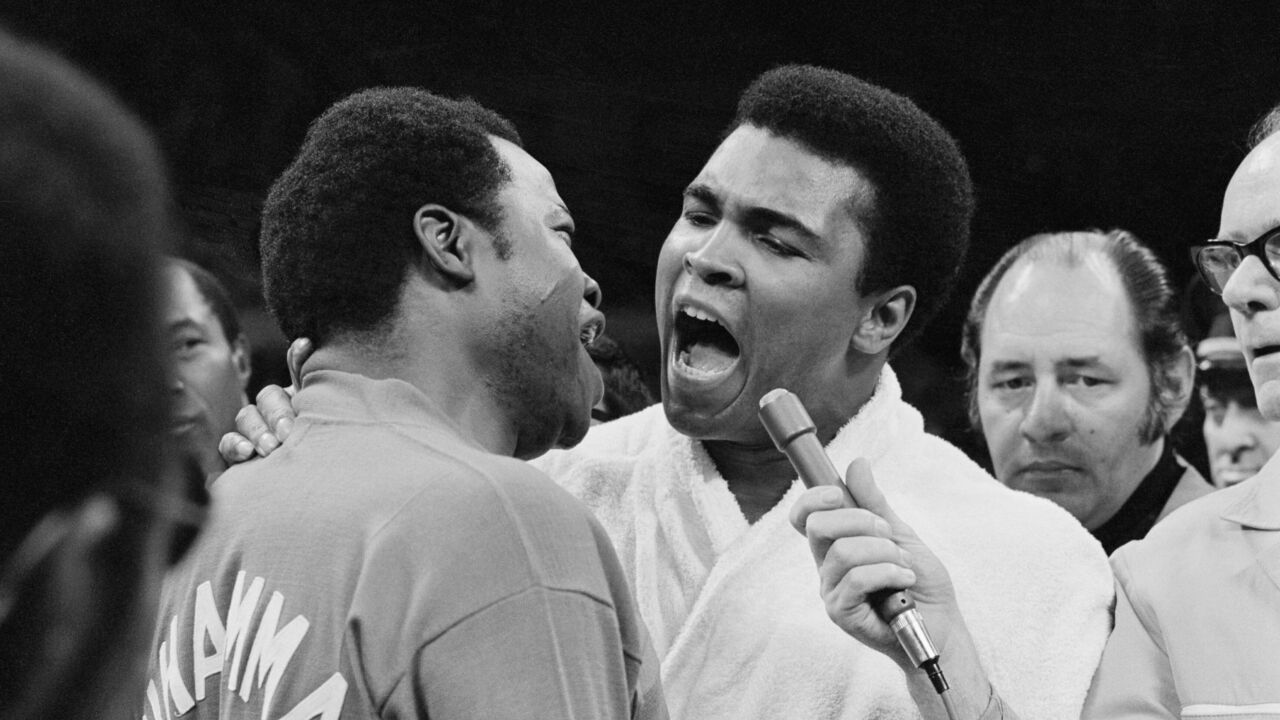

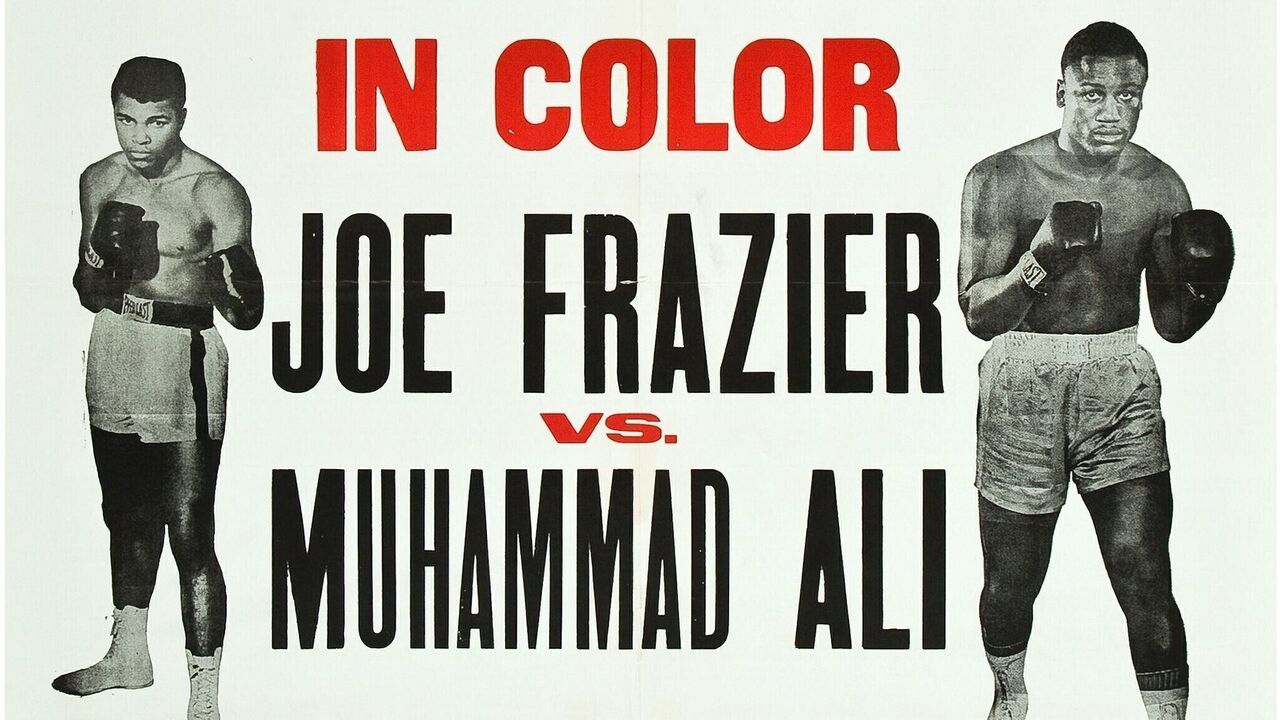

Does anything in sports today compare to the spectacle of Muhammad Ali’s violent, epic championship fights?

I don’t know if there’s ever been an event that was as anticipated as that first Ali-Joe Frazier fight. (Contesting the “Fight of the Century” at Madison Square Garden in 1971, Smokin’ Joe beat Ali by unanimous decision after 15 rounds.)

You have to consider the time, Ali’s place in the culture, the fatigue with the Vietnam War by then, and the sense among some middle-class Americans that Ali was unpatriotic (for refusing the Vietnam draft). You have more people watching the Super Bowl today than would have watched the first Ali-Frazier fight, but it doesn’t have the political ramifications.

Who you were rooting for in that fight said something about what kind of person you were, what your politics were, who your friends were, what your attitude about the country was. It was more true then than, I think, any sports event today.

The American Basketball Association and World Hockey Association courted superstars like Kareem Abdul-Jabbar, Julius Erving, Bobby Hull, and even Gordie Howe in his mid-40s. How did players benefit from the competition these short-lived leagues created?

You’re right: The leagues were almost inevitably short-lived. There was no real research done on whether it would be a good idea to have a pro football franchise in Shreveport, Louisiana, or a hockey team in Houston. But there was new money there. Before the advent of free agency, players had essentially been indentured servants. It gave players a choice.

When Howe was with the Red Wings and winning MVP awards and Stanley Cups, he still had to work a job in the offseason to make ends meet. He had a neighbor who was a businessman who would take his boat to the lake every weekend. Howe couldn’t afford that. When the WHA came offering hundreds of thousands of dollars, Gordie Howe happily took it, and understandably so.

Gordie Howe getting suited up at age 50. You can literally feel the old man strength. pic.twitter.com/9ZirSqG1Qx

— Super 70s Sports (@Super70sSports) November 23, 2022

What did players like Oscar Robertson in basketball, Curt Flood in baseball, and John Mackey in football risk or sacrifice when they fought for free agency to be established?

They risked their careers. They risked their time after retirement within the industry of their respective leagues.

Oscar Robertson was one of the smartest basketball players ever. A lot of people feel he would have been a great coach or general manager. He never got a chance because he was essentially blackballed by the NBA owners for challenging the reserve clause. (Across sports, this stipulation bound a player to his current team even after his contract expired.)

Curt Flood, after a short stint with the Washington Senators, never really got another chance to work in baseball, even though he was a veteran who was very accomplished and knew the game well. John Mackey never got a coaching opportunity after his career ended with the Baltimore Colts. It was stark. It was obvious.

In each of those major sports, the athletes who were risking their careers were African-American. I asked the Steelers’ Hall of Fame defensive lineman Joe Greene about that. He said it probably wasn’t a coincidence. He thinks the Black players, partly because of the civil rights movement, were more keenly tuned in to issues of freedom and choice and options.

Because of that, the Floods, the Mackeys, the Robertsons were more willing to take that step. Athletes of today have followed in their footsteps and should appreciate the sacrifices they made.

You mentioned Joe Greene. He won four Super Bowls with the Steelers dynasty and starred in a legendary Coca-Cola commercial. What place did the athletes of the ’70s occupy in pop culture?

People started to see athletes as performance artists, if you will. Entertainers.

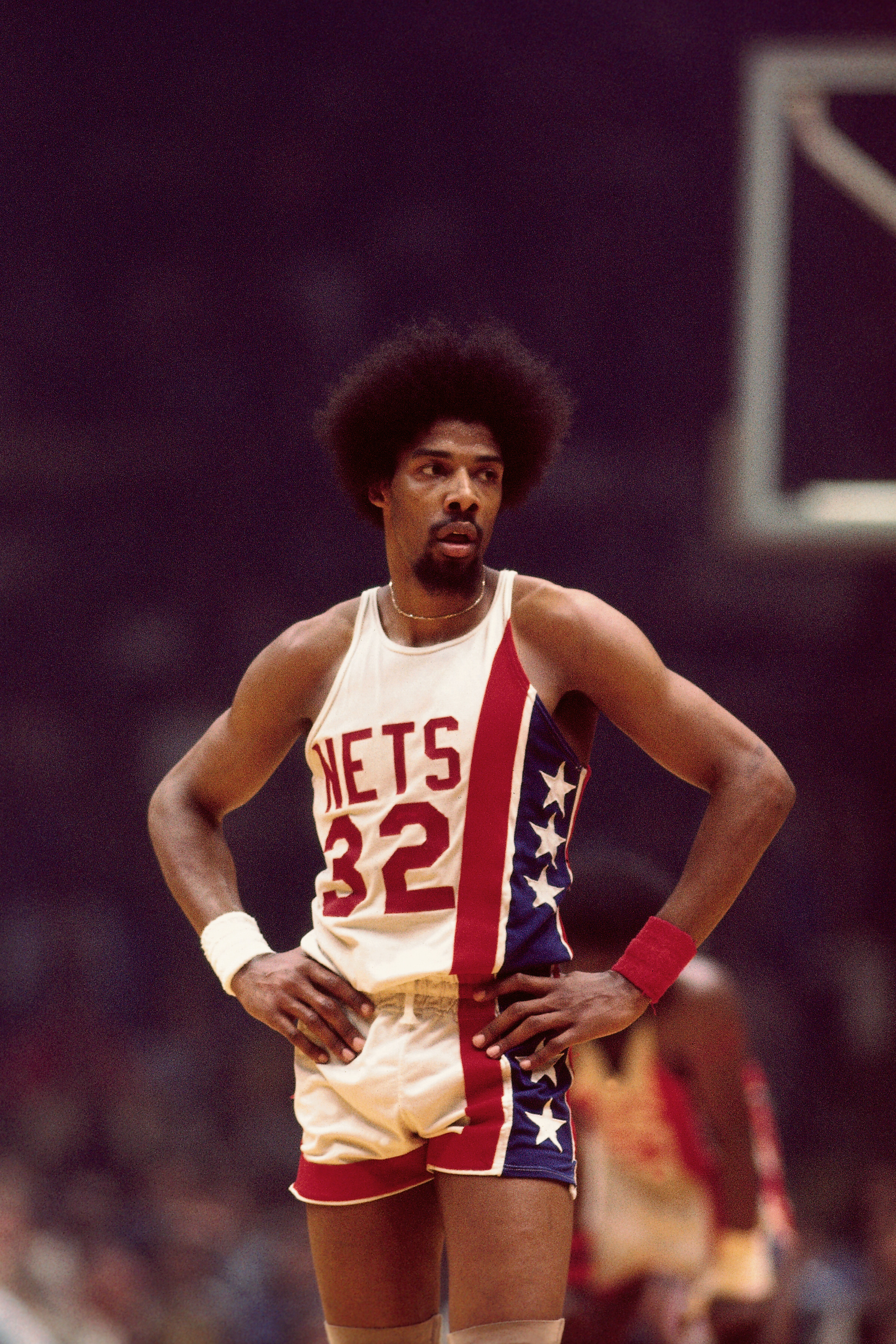

When you look at the last truly mythic figure in American sports, Julius Erving, during his days in the American Basketball Association, that was not just about being a wonderful basketball player. The thing that drew fans to Erving was the way he played basketball. He was a performer in the same way that (the great ballet dancer Rudolf) Nureyev was a performer.

I can remember talking to Hubie Brown, who coached the Kentucky Colonels, one of the Nets’ great rivals during the ABA years. He said he had to tell his team, “If Erving comes anywhere near the lane, just foul him. I cannot risk him doing some whirling dervish, 360-degree dunk, and turning the home crowd against me.”

Hubie Brown talks about his center Artis Gilmore, one of the best shot-blockers in the ABA, facing off against Erving, and Erving at 6-foot-6, who gave eight inches away to Gilmore, elevating above Gilmore. His armpit is above Gilmore’s head as he’s dunking over him. That sense of theater, moment, drama, performance – that sense of, “You have to come here, you have to see this” – was what made Erving special.

The ABA didn’t have a national television contract. Erving was the last superstar to attain that status without most people in the country seeing him. Like I said, I grew up in Kansas City. Most of the kids I knew in the mid-’70s, their favorite player was Julius Erving. They’d never seen him play. They just saw pictures, heard stories, loved the big afro and the stars-and-stripes Nets jersey. It was clear that he was a departure (from the norm).

The ABA played with a red, white, and blue ball. It popularized dunk contests and the three-point line. In any sport, what was your favorite innovation or rule change to result from the ’70s?

This isn’t a specific rule but an entire sport. Billie Jean King and her husband at the time, Larry King, launched World Team Tennis. It was a really interesting take on tennis, which had historically been a country-club sport and very polite, proper, clapping after the point. King recognized that Americans responded to team sports more than individual sports. If you could make tennis a team sport, you could reach a broader cross-section of people.

Those early years of World Team Tennis, they had an innovative scoring system. You played five sets: men’s singles, women’s singles, men’s doubles, women’s doubles, and mixed doubles. You didn’t score by the sets won. You scored by the number of games won. If you lost two sets 6-4 but won the third set 6-1, you are now up 14-13.

You had to win the last game to clinch the match. There are these great fifth-set stories of teams coming back and running off four, five, or six games in a row to send it to sudden death. Crowds really got into it.

World Team Tennis had two challenges. It was trying to fit into a very crowded tennis schedule, and it also was launched before the age of cable television. If it would have launched a decade later, we might still be following World Team Tennis in the spring in the United States.

On X, formerly Twitter, @Super70sSports celebrates the decade’s eccentricities. How often do you check out that account?

When asked if he preferred grass or Astroturf, Tug McGraw said “I don’t know. I never smoked any Astroturf.” pic.twitter.com/76L6SMzYRg

— Super 70s Sports (@Super70sSports) October 10, 2023

I love it. I even mention it in my bibliographic essay. Ricky Cobb does a great job there. It speaks to how wild and off the grid some of the aspects and athletes from that decade were.

There’s a tendency to attribute innocence to any past era. After spending two and a half years on this book, I think it would be incorrect to describe the ’70s as an innocent era. It was certainly a less self-conscious era. Hair was long. Inhibitions were low. There was shag carpeting on the walls.

One thing I tried to do with the book was put all of the changes into a broader context. Sports moving to prime time on network television. Free agency giving athletes a measure of liberation. Integration becoming more the rule than the exception. Women getting involved in unprecedented numbers as athletes, coaches, administrators, journalists. But there were still things that happened in the ’70s that didn’t make any kind of sense.

There was a picture in one of Billie Jean King’s autobiographies. It was a little bit after the “Battle of the Sexes” that she’d won. She’s on this Hollywood soundstage. She’s dressed in frontier, “Little House on the Prairie” garb. She’s sharing a dance with the Penthouse magazine editor Bob Guccione on “The Sonny and Cher Comedy Hour.”

I don’t know what led to it, but it was something that happened in the ’70s. I think the takeaway is there was more living than thinking done during that decade.

Nick Faris is a features writer at theScore.