NBA's 2nd apron explained, and the big questions it prompts

You’ve surely heard by now about the NBA’s dreaded second apron. A new addition to the collective bargaining agreement that took effect a year ago, the second apron has already loomed large this summer as the league’s highest spending teams try to navigate the punitive new realities of life atop the Association.

Let’s dig into what exactly the second apron is, and how it could change the NBA as we know it.

Second apron explainer

Unlike the NFL and NHL, there’s no hard salary cap for NBA teams. In fact, most teams spend each season over the “soft” cap, because teams can exceed that limit to re-sign their own players, and to sign recent draft picks and minimum-contract players.

There’s then a luxury tax system to punish teams that go too far over the cap, and a repeater tax designed to punish teams that exceed the tax threshold (approximately 121.5% of the salary cap) in three out of four years. Essentially, the further you go into the tax and the more often you do so, you pay an increasingly higher penalty on every dollar spent. That’s how a team like the 2023-24 Warriors can end up paying nearly $177 million in luxury tax payments despite being “only” $42.5 million above the threshold.

There are also various exceptions teams can use to sign players, depending on whether they are taxpayers, non-taxpayers over the cap, or have room under the salary cap.

Under the old CBA, teams that used certain exceptions or acquired a player via sign-and-trade were hard-capped at a number called “the apron.” The new CBA has two aprons.

There are still ways for teams to hard-cap themselves at one of the new aprons, but the real story is what happens to teams that can and do exceed them.

The first apron, approximately 126.7% of the salary cap (after applying this formula), comes with its own share of new restrictions. First-apron teams can no longer sign bought-out players who made more than the non-taxpayer mid-level exception (roughly $12.8 million in 2024-25) before being waived. They also can’t take back more salary than they send out in trades, and they can’t use trade exceptions that were created the season prior.

The second apron, approximately 134.4% of the cap, is the real game-changer. In addition to those first-apron restrictions, second-apron teams can’t use the mid-level exception, can’t trade multiple players in the same deal, can’t sign-and-trade their own players to acquire others, and can’t send out cash in any trades.

Finally, teams above the second apron at the end of the regular season will have their first-round draft pick seven years out frozen so that it can’t be used in any trades. The only way to unfreeze it would be to duck the second apron in at least three of the next four years.

For example, if a team’s above the second apron on the last day of the 2024-25 season, its 2032 first-rounder will be frozen, and the earliest the pick could be traded would be after the 2027-28 season. However, if a team remains above the second apron in at least two of the four years after having its pick frozen, that frozen pick moves to the bottom of the first round, no matter how poorly the team performs.

The roster-building restrictions are already crippling enough, but those delayed draft-pick ramifications could be devastating for teams in the long run. So, you can see why no one wants to cross that second apron, other than teams reaping the benefits of surefire contention.

Now that you (hopefully) understand the complexities of the NBA’s latest cap, tax, and apron model, let’s get to some important questions.

Was this truly necessary?

It depends who you ask.

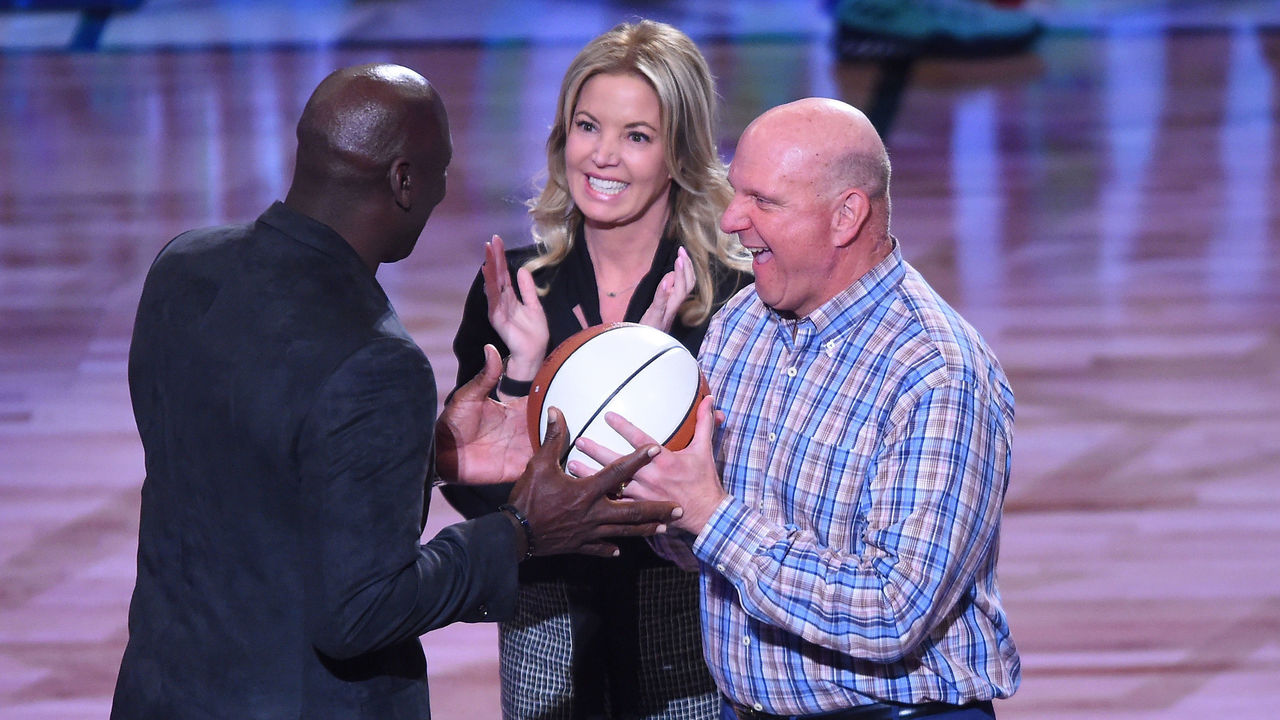

The league continues to cite competitive balance as the end goal, and the CBA does discourage people like the Clippers’ Steve Ballmer – the richest owner in pro sports with a net worth of $132.2 billion – from blowing past the tax threshold in ways even other billionaires can’t. But spending big has never had a 100% success rate (just ask Ballmer). Plus, with six different champions in the last six years, the NBA is already enjoying nearly unprecedented parity.

Off the court, in addition to other means of revenue sharing, half the money raised from luxury tax payments is dispersed among non-taxpaying teams, who themselves are incentivized to spend at least 90% of the cap.

In other words, the playing field already looks pretty level from here. It seems the owners came up with a scheme whereby they can spend less without the public scorn that usually accompanies such penny-pinching.

Every CBA includes a new wrinkle to protect the owners from themselves. In that regard, perhaps more punitive measures were necessary. Using salary cap history from RealGM and team spending data from Spotrac, we can see the number of teams spending at second-apron levels has increased substantially in recent years:

In the first 10 years of Spotrac’s data, between zero to four teams each season – an average of 2.2 teams per year – spent at least 134.4% of the cap. In the last three seasons, at least five teams – an average of 5.7 per year – spent at second-apron levels. The Suns, Timberwolves, Celtics, and Bucks are currently projected to be second-apron teams in 2024-25.

With an outrageously lucrative new media rights deal on the horizon and the cap projected to rise by a maximum of 10% every year, team owners should be thrilled they’ve imposed stricter limits on themselves.

Did the players actually lose this deal?

Not really. While it’s true that fewer owners will spend at second-apron levels, the CBA guarantees that players collectively earn 49-51% of all basketball-related income (BRI) the league generates. In addition, team and league licensing revenue is now included in BRI, which was a win for the union. The players are still getting their share of the pie, despite the penalties for high-spending teams.

Will the second apron act as an unofficial hard cap?

Probably not. The same teams that already treated the tax threshold as an unofficial hard cap will continue doing so, and more clubs will understandably be wary about exceeding the aprons. But the temptation of genuine championship contention (and the revenue that comes with it) will still lure a team or two into the abyss. Teams will just have to be more selective about when to go for it.

The real question is how long teams are willing to remain over the second apron while contending. Which brings us to:

Unintended consequences

In a quest to discourage high-priced superteams, the NBA may have shot fledgling homegrown juggernauts in the foot. While it’s possible that a cap growing at a faster rate than the year-to-year raises in player contracts could aid these teams, it seems inevitable that the second apron will lead to the breakup of well-built teams whose organizations scout, draft, and develop well.

You can argue it’s already happening in Denver, where the Nuggets let Bruce Brown and Kentavious Caldwell-Pope walk in the two years after winning the franchise’s first championship, which also happened to be the first two offseasons under the new rules.

Even while contending for titles, how many years will the Celtics’ next ownership group accept second-apron penalties before splitting up the two Jays? Jayson Tatum and Jaylen Brown currently own the two biggest contracts in NBA history. Once Jalen Williams and Chet Holmgren graduate from their rookie-scale contracts to join Shai Gilgeous-Alexander on max-level deals in a couple of years, will the Thunder be able to keep their young trio together?

The league will eventually have to consider how to protect such homegrown teams from the full scope of the apron’s wrath. What if only a portion of salaries belonging to players drafted by their incumbent teams counted toward the aprons?

Was Brunson’s sacrifice a sign of the times?

Another fascinating development to monitor is how max contracts evolve in the age of the second apron. Jalen Brunson signing a maximum $156.5-million extension this summer rather than waiting for the chance to sign a $269.1-million max next year caused quite a stir. But there’s more to that decision than meets the eye.

As an undersized guard who plays a physical brand of basketball in Tom Thibodeau’s demanding system, Brunson jumping at the opportunity to sign his first real megadeal makes sense. He can also hit free agency again earlier to make up some of the difference between the two contracts. But the consequences of the second apron can’t be ignored here. Providing the Knicks with future flexibility to maintain a contending-level roster played at least some part in Brunson’s decision.

Brunson surely won’t be the last star to make such a sacrifice in support of his team’s roster-building efforts. Further, you can bet teams will try to use Brunson’s extension as a precedent in their own negotiations. Finally, the agreement between Brunson and New York could signal a changing tide when it comes to max contracts. Whether it’s shorter max deals for second-tier superstars or no max at all for mere All-Stars, teams will likely be more selective when handing out the biggest contracts available to them.

With the aprons and future flexibility more important than ever, we may be entering a world where full max contracts are reserved for only the very best of the best. Will we see fewer and shorter versions of mid-level contracts?

The players will always get their agreed-to share, as mentioned, but the way that share is dispersed may be changing.

The big question

If the new CBA has the desired effect of prolonging and enhancing the NBA’s current run of championship parity, what does that mean for the league’s popularity and future?

The NFL dominates the American sports landscape regardless of which teams are on top or which markets are featured, but there’s no precedent for the NBA thriving without superstar-laden superpowers. The only other time the league crowned six different champions in six years was the second half of the 1970s, and that dull run coincided with the Finals being broadcast on tape delay until Magic Johnson’s Lakers and Larry Bird’s Celtics breathed life into the enterprise.

Of course, the sports world and the media landscape have changed greatly since then. The NBA’s international appeal, the rise of social media, and the way sports are consumed across a variety of platforms means the league isn’t as dependent on the success of specific teams or players. But a league of 30-plus mediocre squads isn’t great drama, either.

Does a more balanced NBA, where teams rise and quickly fall before dealing with the penalties of getting too expensive, lead to more league-wide interest? Or does more frequent roster turnover and no dynastic superteams lead to a league full of teams – and a league itself – without an identity?

In a letter addressed to the NBA’s board of governors criticizing revenue sharing and the league’s new media rights deal, oft-aggrieved Knicks owner James Dolan wrote, “We are well on our way to becoming a one-size-fits-all, characterless organization.”

Maybe this one time, Dolan has a point.

Joseph Casciaro is theScore’s senior content producer