'I would've fought him': Inside Roy Keane's turbulent managerial career

Find the biggest stories from across the soccer world by visiting our Top Soccer News section and subscribing to push notifications.

Warning: Story contains coarse language

Steven Caldwell vividly recalls the moment his Sunderland career effectively ended. He was grocery shopping with his wife when the phone rang. Roy Keane, the Black Cats manager, was on the line. The conversation was abrupt.

“‘I spoke to Burnley. They put an offer in for you, and you can leave,'” Caldwell, then Sunderland’s captain, remembers the combative Keane saying. “I was like, ‘What? I thought you wanted me to stay.’

“‘Well, I’ve changed my mind. I want you to go.'”

Just two days prior, a tense meeting between the pair ended with Keane telling his skipper, an impending free agent, that he’d sort out a new contract to keep him at the club. Volatility, Caldwell told theScore, was commonplace with Keane.

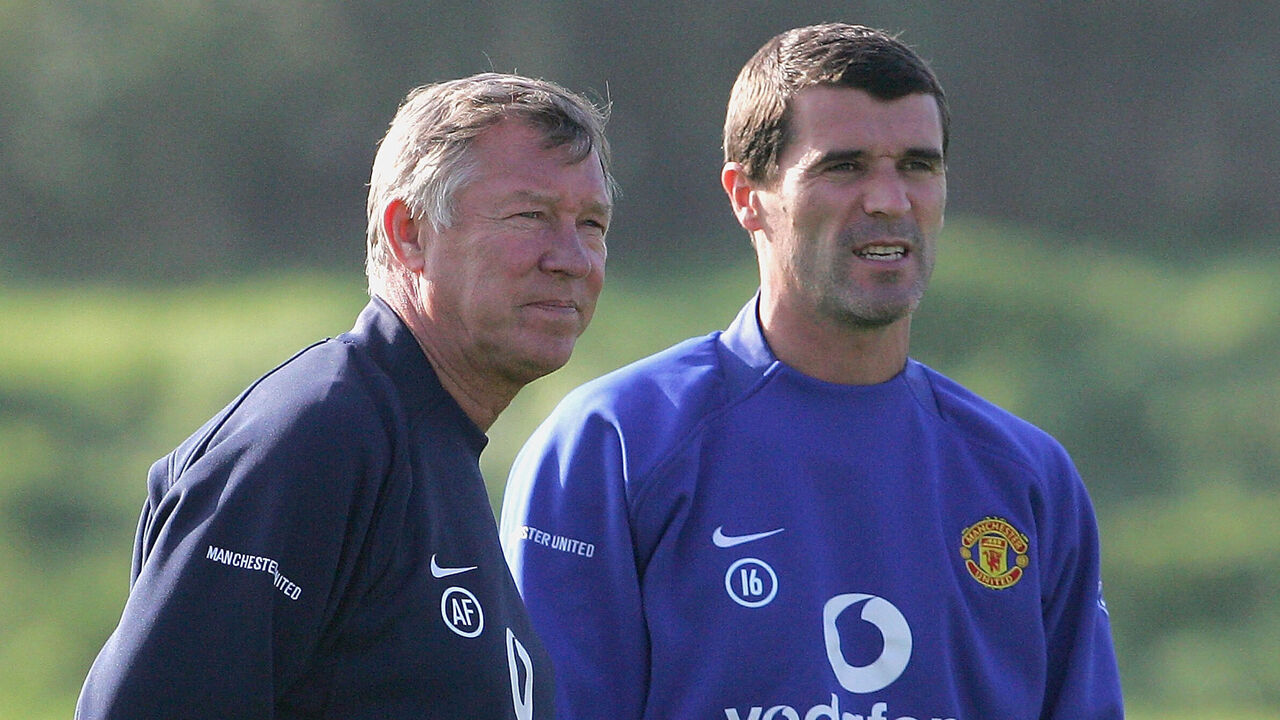

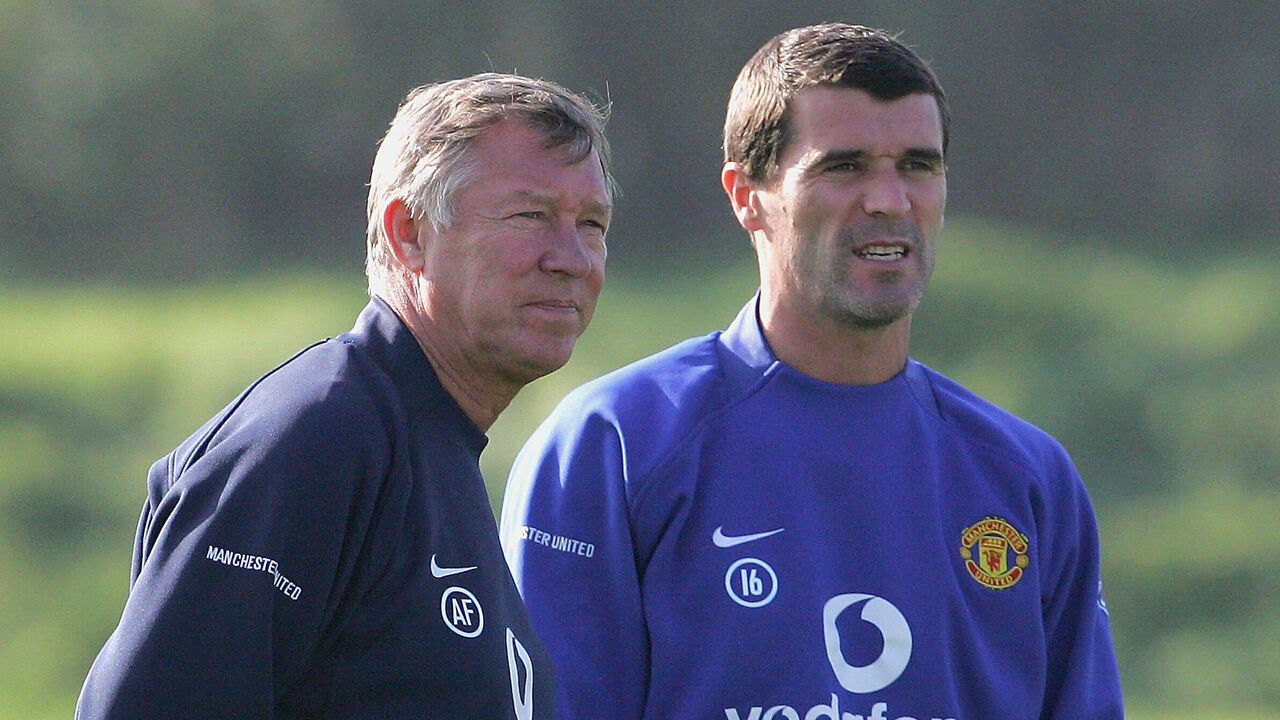

The Manchester United legend’s appointment surprised some Sunderland players to begin with that season. In his first job as a manager, he was entrusted with a side that opened the 2006-07 campaign with five consecutive defeats following a historically poor relegation from the Premier League.

But the club hadn’t just placed its trust in any rookie boss. Keane was notoriously feisty on and off the pitch. Niall Quinn, the Sunderland chairman and icon overseeing the team until he hired Keane, witnessed the latter’s infamous, searing rant at Republic of Ireland boss Mick McCarthy ahead of the 2002 World Cup. Quinn, one of the senior Irish players at the time, supported McCarthy in the rift, which ended with Keane sensationally leaving the squad prior to the tournament.

“Quinny doesn’t suffer fools gladly, but he’s not volatile. He’s totally measured and controlled. Roy’s also smart, but not measured and controlled,” Caldwell said.

The public spat, which stemmed from Ireland’s supposedly poor World Cup preparations, was perhaps the biggest controversy of Keane’s storied playing career. Ireland and the rest of the British Isles were gripped by the soap opera that unfolded. The “Saipan incident,” as it was dubbed, has its own dedicated Wikipedia page.

That wasn’t all, of course. There was also Keane’s infamous challenge on Manchester City’s Alfie Haaland – father of Erling Haaland – that led to the midfielder’s early retirement. He flung his elbows, stomped on genitals, and grappled with opponents and teammates. His legendary spell of over 12 seasons with Manchester United ended abruptly due to his faltering relationship with manager Alex Ferguson.

“He wasn’t bothered about upsetting people,” Tommy Miller, who worked under Keane at Sunderland and Ipswich Town, said. “That’s how he played as well. He’ll tell you himself: There’s no friends in football. I don’t think he had many friends.”

‘Our best player was the manager’

Sunderland followed four straight losses to begin the 2006-07 Championship season with an embarrassing League Cup elimination at Bury, who were sitting dead last in the fourth tier of English football.

After that harrowing defeat, a visibly emotional Quinn revealed a managerial appointment was imminent. Grudges were going to be set aside.

“Let’s be honest, it worked,” Miller said.

Keane’s arrival revitalized a squad that had been drained of confidence. He met the players during a Sunday training session and watched from the stands the next day as Sunderland beat promotion candidates West Bromwich Albion. Even Quinn, in his last appearance as a manager, couldn’t hide his amazement.

“People thought we were going to get spanked again today,” he said.

Keane wasn’t afraid to make changes despite the much-needed victory. He dropped five players from the starting lineup for his first official game as Sunderland boss, a trip to Billy Davies’ Derby County, and hailed the team’s character after a 2-1 comeback win. Although the Black Cats collected all three points, defender Neill Collins – who scored in the win over West Brom – wanted to know why he was demoted from starter to unused substitute against Derby. The center-back, who had recently turned 23, thinks he was the first player to initiate a one-on-one meeting with his new boss.

“People always fear the worst with Roy Keane – but he was excellent,” Collins recalled.

Collins, who’s now in charge of Barnsley, was impressed with Keane’s man management. Keane told the young Scot to be patient and insisted he was part of his plans. The manager then gave Collins a full 90-minute shift for Sunderland’s next outing, deploying him at right-back for the first time in his career in a 3-0 win at Leeds United.

Training became more intense. Assistant manager Tony Loughlan covered most of the sessions while Keane, perhaps taking inspiration from Manchester United’s Ferguson, would observe from afar or arrive later in the day. He had high standards and would occasionally step in with directives and demands. He wanted high-tempo, attacking football. He urged his players to take only one or two touches. He fired the ball at their feet during rondos.

Keane was 35 and suffered some injury issues during his playing days – but his quality on the ball hadn’t deserted him. Far from it.

“It was maybe the first three weeks he hadn’t joined in at all, but he joined in a game, and I think his team won 3-0 and he scored all three. It was incredible,” Collins said.

“Our best player was the manager,” he added.

Quinn and the rest of the boardroom were willing to back Keane in the transfer market, allowing him to retool his roster before officially taking charge. Sunderland signed six players on the last day of the summer transfer window alone, and only one – Keane’s former Manchester United teammate Dwight Yorke, who had just flown across the world to join from Australia’s Sydney FC – didn’t start against Derby.

“He had whatever he needed that first season,” Caldwell said.

theScore’s attempts to contact Keane through agents who look after his commercial interests and public speaking engagements were unsuccessful.

Out of favor

Players Quinn signed earlier in the summer, like Clive Clarke and Arnau Riera, soon disappeared from view as Keane brought in his own personnel. Remnants from the previous regime – headed by Keane’s old rival McCarthy – were even more vulnerable.

Miller was proven in the Championship, notching 11 and 13 goals from midfield over his previous two second-tier seasons. He was also desperate to perform for Sunderland, the team he regularly watched with his dad and supports to this day.

“I was doing everything right,” he said. “I was training well. I was doing well for the reserves. In in-house practice games, I was scoring goals.”

But Keane wasn’t convinced.

Miller, who was injured when Keane arrived, was sent on a short-term loan to fellow Championship side Preston North End in November 2006 and was strangely eligible to face Sunderland at the end of December.

That dubious decision – or oversight – backfired. Preston dealt Sunderland their second defeat in three matches to finish in second place at the season’s halfway point and leave Keane’s men 10 points below the automatic promotion positions. Miller played the whole match.

His frustration at not being given an opportunity under Keane made it easier to offset his loyalties toward Sunderland.

“Because of Roy Keane, I just thought, ‘Yeah, fuck you.'”

Miller returned to Sunderland in January and made his only appearance for Keane as a substitute the following month. He suspects his opportunity only materialized because Keane instructed the team bus to leave without three players who were running late.

Caldwell wasn’t frozen out in the same way. An injury sidelined him during the start of Keane’s tenure, but he was soon thrust into the starting lineup when he was fit. He remained captain.

That’s what made Keane’s U-turn, when he blindsided Caldwell at the grocery store, more perplexing.

Even after a positive few hours touring Burnley’s facilities, Caldwell wanted to fight for his place at Sunderland. But Keane wouldn’t change his mind again. He called Caldwell into his office to question why he’d not accepted a “great offer” from Burnley. That irritated Caldwell – he and his family would judge the quality of the offer – and he was soon pushed to breaking point when Keane told him he’d strip him of the captaincy because he wanted players who were “up and at it.”

“He’s probably the only guy in 18 years as a professional – player, coach, anyone – that’s ever questioned my attitude. Ever,” Caldwell said.

“I swear to God, I would’ve fought him in that room if he stood up, if he was ready for it. I was so angry.”

Caldwell thinks there were around 10 minutes left in the January transfer window when he joined Burnley.

Despite upsetting players with his squad overhaul, Keane got Sunderland promoted as champions. It was an incredible feat considering the mood in the camp and team’s position in the table when he took over, but was it primarily recruitment, rather than Keane’s management, that sparked their return to the Premier League? Their spending outstripped most of their Championship rivals, and it didn’t slow after promotion – but Keane’s Sunderland struggled to stay afloat in the ultra-competitive Premier League.

They avoided relegation by three points in their first season back in the top flight. When Keane left by mutual consent in December 2008, Sunderland were 18th after five defeats in six matches. They’d splurged almost £70 million on 33 players during Keane’s 27-month reign.

Quinn praised Keane effusively when he departed.

“He was instrumental in developing a winning mentality – that was the toughest thing of all for him to come and do when we were at the foot of the Championship,” Quinn explained. “He brought standards to this club which are amazing.”

Playing with fear

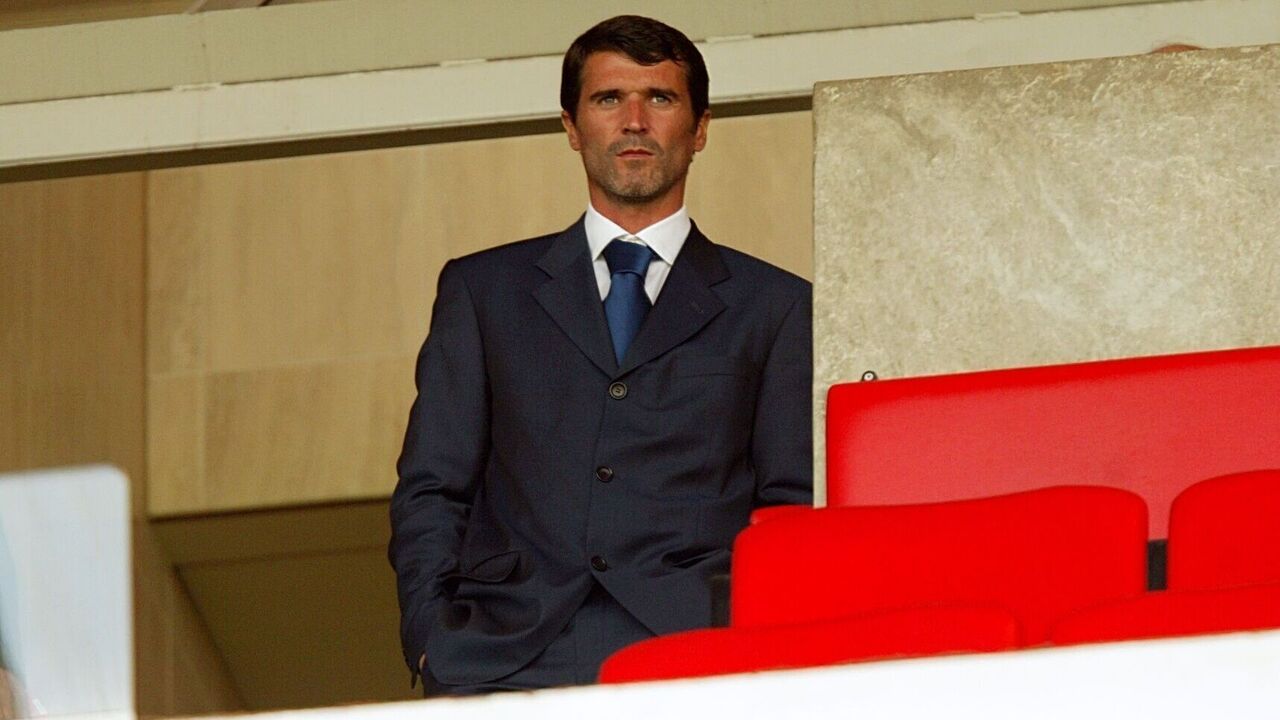

Keane wasn’t out of the game for long.

Twenty weeks later he embarked on a similarly ambitious project at Ipswich Town. Keane had the luxury of assessing his squad over the final two matches of the Championship campaign before truly kickstarting the Tractor Boys’ bid to return to the Premier League over the summer.

“We went to an army camp. We had to survive three days in the woods,” Pim Balkestein, then 22, said of the team’s rigorous preseason getaway ahead of the 2009-10 campaign.

Balkestein remembered Keane joining the drills and appearing to enjoy them. Explosive, gun-like sounds would startle the squad awake in the early hours, signaling another grueling day in the wilderness. Balkestein believes the exercises helped them “grow together as a group,” but that wasn’t evident when the season got underway.

Keane’s Ipswich started in miserable form, recording eight draws and six defeats before finally winning their first match on the final day of October. Balkestein was taken aback by Keane’s ferocity in the Ipswich dressing room during that run. Objects would fly. He would scream. The youngster said the “really nice guy during the week” could switch in an instant.

“When you play a shit ball, he’ll really say, ‘You’re a fucking wanker, why (did) you play this shit ball?’ You have to cope with it,” Balkestein said.

Owen Garvan, who was substituted 23 minutes into a match at Watford after making an error, said people “stayed clear” of Keane to avoid his outbursts.

“Your confidence levels are going lower. You’re scared to make mistakes,” Balkestein, who was soon shipped to Brentford, recalled of his mental condition. “You’re thinking about what Roy Keane’s thinking, and that’s not the state of mind you need to have on the pitch.”

Balkestein suggests Keane’s inability to adapt to different personality types harmed his tenure in Suffolk. Ipswich finished 15th at the end of Keane’s first full campaign, closer in points to the relegation zone than the playoff places. He was sacked midway through the following season, with Ipswich writhing in 19th place.

“I tracked some players, and I think from that squad, 10 players reached Premier League clubs, so there was a good squad,” Balkestein said. “Maybe he didn’t bring it together.”

Keane hasn’t overseen a team since.

He was assistant manager of Ireland from 2013-18 and was briefly on the coaching staff at Aston Villa in 2014 and then Nottingham Forest five years later. There’s been nothing after that.

Caldwell believes one of his former boss’ greatest hurdles to managerial success was separating “Keano” the aggressive midfield star from Keane the gaffer. He had a reputation to live up to as a no-nonsense, outspoken character, and his scathing dressing-room addresses and ruthless discarding of players satisfied that role.

And as a pundit with a delivery that’s blunt, savage, and often the key ingredient for viral videos of Premier League analysis, he could still be trying to play a part.

“The reason he’s great on the telly is actually what you saw in management. I think he started to become a caricature of himself,” Caldwell said.

“He’s good value on TV, but it’s all a big act.”