Is the Thunder's overload defense going too far?

One of the hardest things for an NBA team and coaching staff to do is stick with a tactical process when it yields a bad result. Over the course of this season, Coach of the Year Mark Daigneault and his precocious Oklahoma City Thunder have shown a lot of conviction in their principles and play style. But those convictions were tested in their Game 2 second-round loss to the Dallas Mavericks, and it’ll be interesting to see if they adjust moving forward.

The Thunder won Game 1 with an exaggerated defensive scheme that flooded the strong side and loaded up on Luka Doncic, Kyrie Irving, and the roll men on the other end of their of ball-screen actions. The intent was to limit what the Mavs’ two best creators could do, send early low-man help to force dive men Daniel Gafford and Dereck Lively to either finish through traffic or fall back on their underdeveloped short-roll playmaking, and live with the open threes they conceded to Dallas’ role players as a result.

It worked. The Mavs’ offensive rating in the game was an even 100, their lowest mark of the playoffs so far and lower than all but five of their games during the regular season (excluding their last two, when they rested all their starters). They shot just 34% on that buffet of open threes, and committed 15 turnovers. A hobbled Doncic was limited to 6-of-19 shooting. Irving had more turnovers than assists. Gafford and Lively, who both shot over 74% from the field during the regular season, combined to go 6-for-15.

In Game 2, that same overload defense was demolished by P.J. Washington, Josh Green, and Tim Hardaway Jr., who combined to shoot 12-of-20 from 3-point range. Doncic also rediscovered his mojo and hit five threes. Dallas slightly tweaked its weak-side spacing, cut down on its turnovers, and finished with a 122.7 offensive rating to even the series.

The question now is whether the Thunder should actually change anything or stay the course. Because even in the loss, their scheme worked exactly as intended. Though Doncic got going, Irving finished with only nine points and used fewer true shooting possessions than Washington, Hardaway, and Derrick Jones Jr., which feels like a trade-off OKC can live with. Gafford had a bit more success in Game 2, but Lively continued to struggle on the short roll against the early tags, shooting 1-for-7.

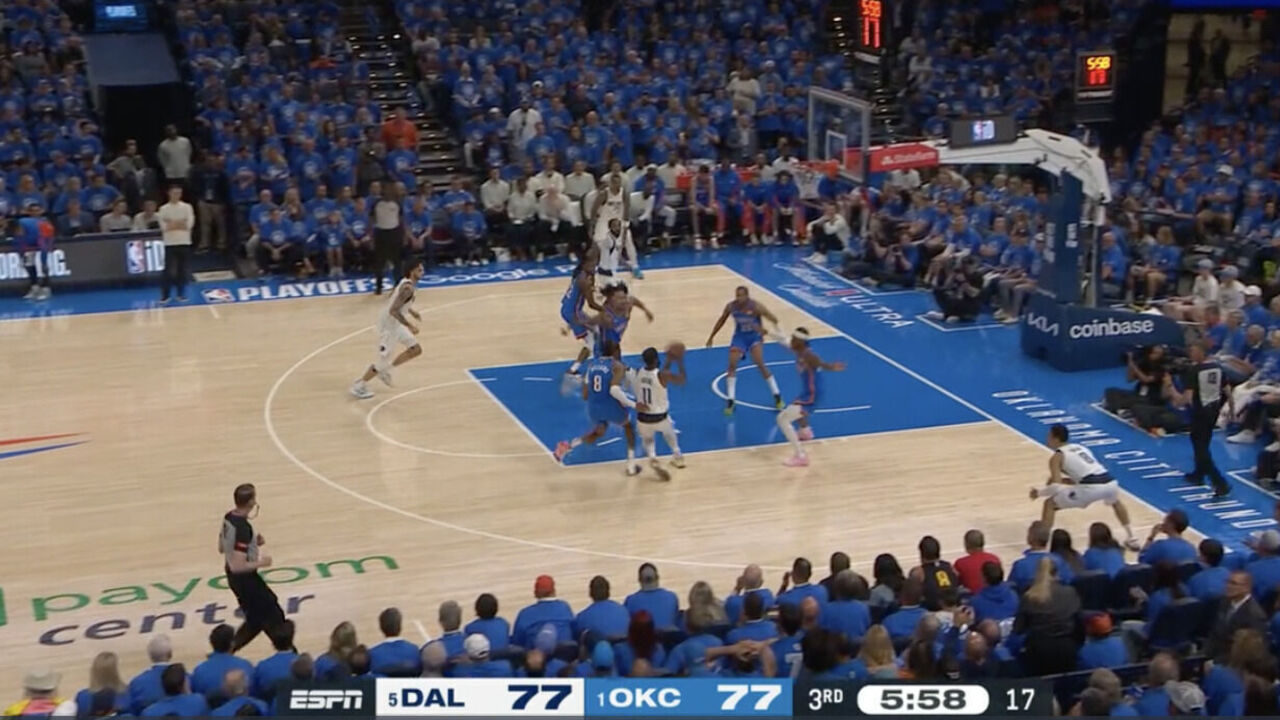

At the same time, there were probably a couple of spots in which the Thunder could’ve afforded to scale back their help. For example, did Shai Gilgeous-Alexander really need to make a full rotation off the strong-side corner (rather than a token stunt) against Irving’s drive, pictured below, considering there were already two blue jerseys in the paint?

The Thunder climbed all the way back from 14 points down, but after Green canned that go-ahead three off an easy kickout from Irving, the Mavs never trailed again. OKC conceded a league-high 12.1 corner 3-point attempts per game this season. In Game 2, Dallas attempted 19. Where’s the tipping point?

That doesn’t mean the Thunder will or should completely reorient their help principles. They do a lot of things that buck the unwritten rules of defense, and that largely works to their benefit. One such rule is: “Thou shalt not help off the strong-side corner,” which is a rigidity OKC rightly rejects, even if it occasionally swings too far in the opposite direction. When it comes to defending the pick-and-roll, and specifically tagging the roll man, the Thunder are less concerned with weak side vs. strong side than they are with the number of offensive players on each side, and the shooting quality of those players.

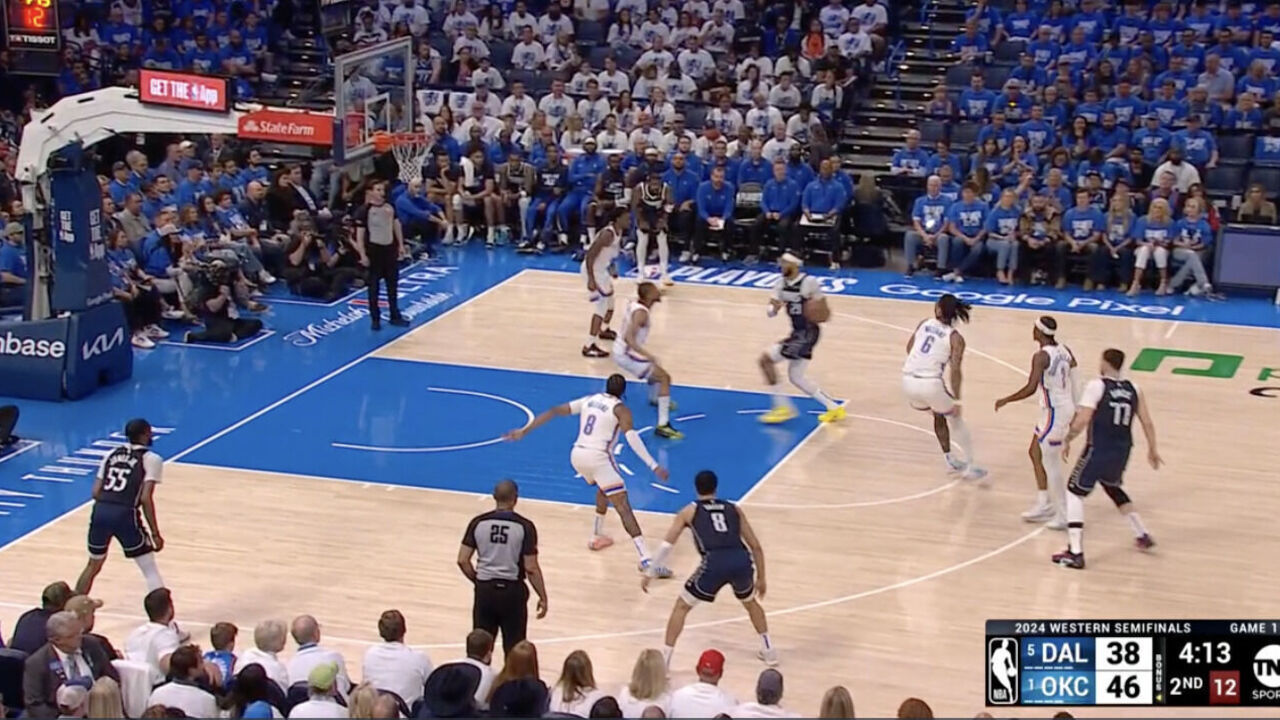

Take this possession from Game 1, for example:

The Mavs ran a high Doncic-Gafford pick-and-roll on the play, with Gafford setting the screen all the way out at the logo. With Thunder backup center Jaylin Williams playing a high drop and meeting Doncic at the 3-point line, Gafford rolled behind him and caught Doncic’s pass in stride. But Aaron Wiggins, pulling way over off of Jones Jr. in the strong-side corner, was already waiting in the lane.

Cason Wallace was the weak-side low man, but he was the lone defender on that side and he was guarding Kyrie freaking Irving. Even with Doncic’s left hand across his body, that skip to Irving is a pass Luka can make in his sleep, and it would’ve been incumbent on Wallace to recover back out after tagging Gafford. Instead, the Thunder still had Jalen Williams to zone up two mediocre shooters in Jones Jr. and Green.

The Thunder have tagged from both sides on a lot of possessions in this series – such is their commitment to jamming up the Mavs’ central pick-and-roll actions. That was inevitably going to lead to them getting burned on the second side at some point, and Daigneault and his staff had to know that. This team’s identity is built on accepting – and winning – various tactical trade-offs.

As I’ve written before, there’s a kind of contradiction at the heart of the Thunder’s unique roster build. They profile as a small team, because they exclusively play wings at power forward and start a center who, despite looking the part from a height perspective, weighs less than a lot of point guards. At the same time, they don’t actually play any small players. Their guards are huge for their positions, and the shortest player in their rotation is 6-foot-4.

While there are some well-documented consequences of that roster build, there are more benefits. We’re getting a great illustration of one of them in this series, as their low men are tasked with so much heavy lifting on defense. Chet Holmgren’s rim-protection has been tremendous, but OKC’s “smalls” also deserve a lot of credit for executing a scheme that has Dallas shooting 48% inside the restricted area, by far the worst of any second-round team.

One of the big drawbacks of playing an aggressive pick-and-roll coverage – whereby a team brings its big man up to blitz or show at the level of the screen – is that it requires smaller players to serve as the last line of defense, tasked with protecting the paint and cleaning the defensive glass on the back side. Even if a team has a big man who excels at guarding in space and disrupting ball-handlers’ progress at the point of the screen, that coverage can be outdone by shoddy or ineffectual low-man work from small guards and wings.

With a starting backcourt of the 6-foot-6 Gilgeous-Alexander and 6-foot-8 Josh Giddey, the tank-like Jalen Williams and Lu Dort on the wing, and guards like Wiggins (6-foot-11 wingspan), Wallace (6-foot-9 wingspan), and Isaiah Joe (6-foot-8 wingspan) off the bench, OKC doesn’t really have that problem. Holmgren is an awesome drop defender, but when the Thunder are facing a dangerous ball-handler like Doncic or Irving, they can bring him up high – or just have him commit to the ball earlier when he’s dropping back – and trust they have enough size, length, and smarts to hold down the fort behind him.

In the third quarter of Game 1, during a crucial stretch that turned the contest’s tide, Giddey and Gilgeous-Alexander stoned Gafford on the roll on back-to-back possessions. In the second half of Game 2, with OKC mounting a comeback, Lively found himself deterred by Wiggins and Wallace.

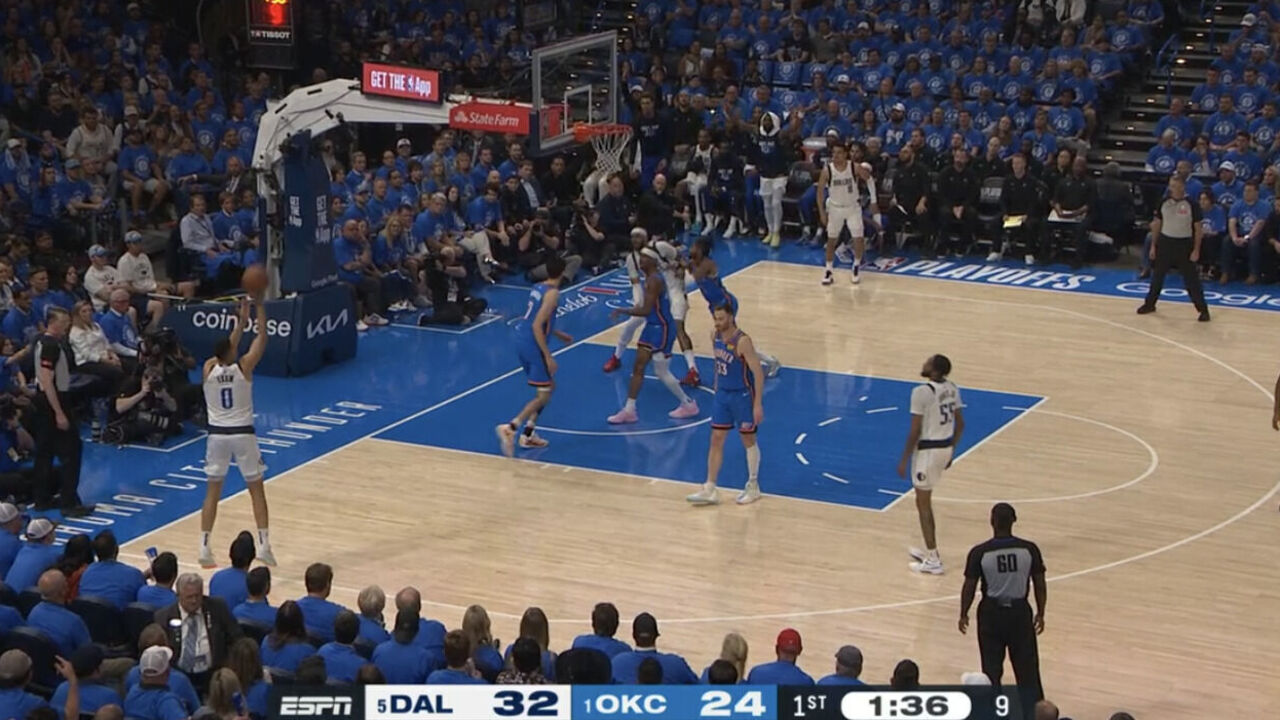

The aggressive defensive scheme has as much to do with the Thunder’s struggles on their own glass this year as Holmgren’s slender build does. But they’ve actually rebounded pretty well so far in this series, and part of that owes to their willingness to completely ignore Dallas’ role players on the perimeter. Look at this:

OKC’s been particularly dismissive of Dante Exum, despite the fact Exum shot 49% from deep during the regular season. Holmgren could’ve closed out to the corner on that play, but instead chose to turn his back to Exum and put a third body on Gafford under the basket. Exum missed, and the Thunder secured the rebound.

As we saw in Game 2, the trade-offs aren’t always going to work out in OKC’s favor. But identities are forged through repetition and commitment to principles, especially when those principles are challenged. Few teams have crafted a more coherent identity than these Thunder. They’ve come too far to reverse course now.