After the exodus: How soccer is fueling Oakland's sporting rebirth

Find the biggest stories from across the soccer world by visiting our Top Soccer News section and subscribing to push notifications.

“Get me the fuck out of this poor-ass city.”

Jorge Bejarano will never forget those words, overheard in a conversation about the Raiders’ future about two years before their wish to leave Oakland became public.

Bejarano was working as a server at an upscale Japanese restaurant in the city when NFL executives met with Raiders owner Mark Davis in a private area at the venue. The area’s seclusion was partly betrayed by its patchy perimeter of bamboo sticks. Davis was asked what he wanted for his franchise.

“That’s exactly what he said,” Bejarano recalled. “And that destroyed me.”

Bejanaro grew up a Raiders superfan. His earliest memory watching football at the Oakland Coliseum was when he was around eight years old. His mother painted his face to look like the Raiders pirate. He remembers taking a ride on the BART, the local transit system, with his father before walking through a tunnel that led to the raucous tailgate parties. He’ll never forget being introduced to Oakland’s iconic – and intimidating – NFL atmosphere.

“(There) was this rag doll of a Kansas City Chiefs person, and it was just being thrown in the air and people were pouring beer all over it and kicking it,” said Bejarano, who moved from Mexico City to Oakland with his family when he was four.

“But yet, as scary as it looked, everyone was so welcoming. It felt like I was part of that family instantly.”

Those bonds tightened. Bejarano’s Raiders fascination grew into an obsession.

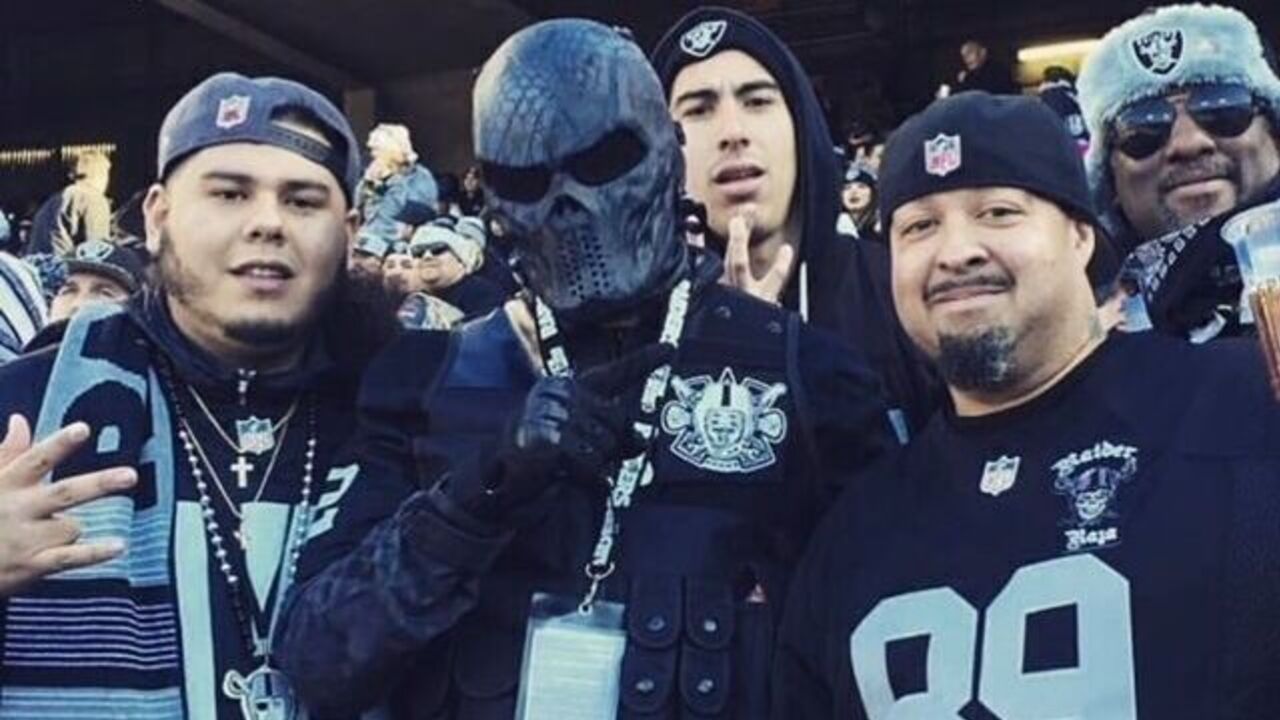

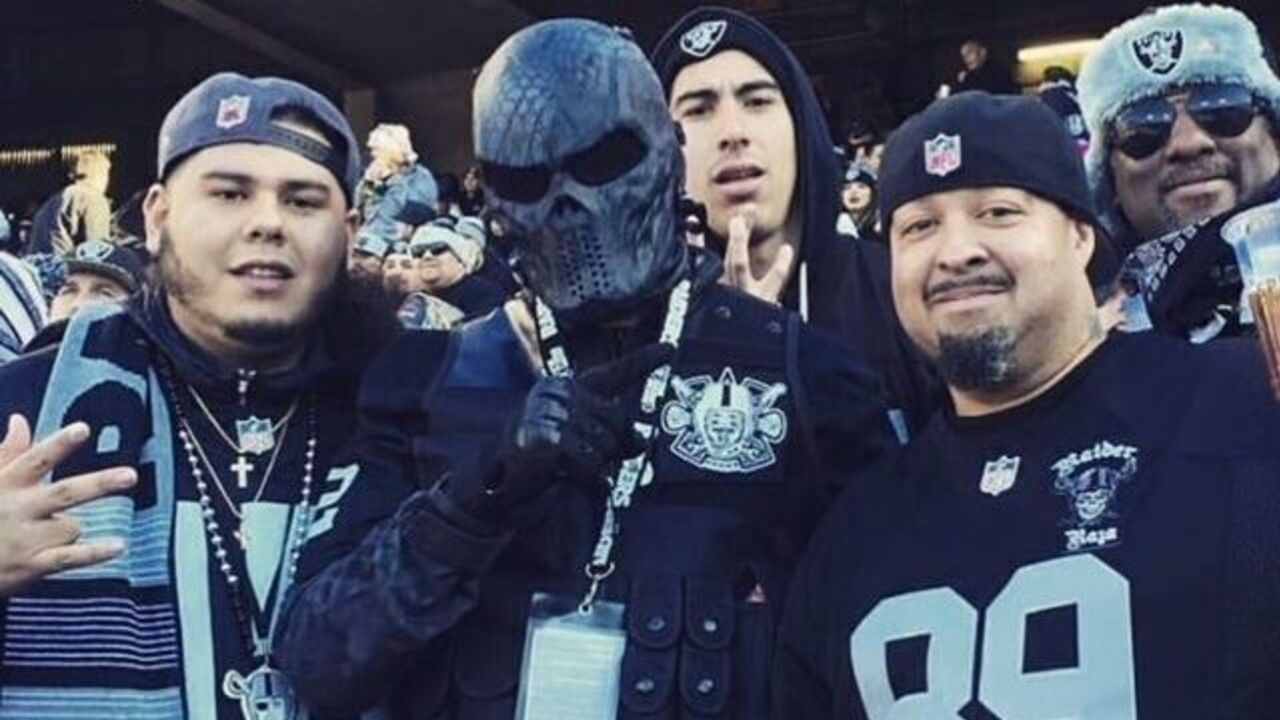

As a kid, Bejarano would ride his skateboard to the Coliseum and often snag a ticket as the game was starting. His passion occupied more time as he got older. Saturday nights and early Sunday mornings would be spent preparing tailgates; beer, ice, and food was needed. He and his friends regularly traveled to watch the Raiders on the road. They yelled and screamed through games, even when their team trundled toward yet another miserable season. He wore a menacing mask and tactical gear embellished with patches and pins. He was known as Savage Raider.

As the Raiders’ departure for Las Vegas loomed, Bejarano and his friends tried to prolong gamedays: earlier starts, and even later finishes. The Raiders’ last home game in Oakland was on Dec. 15, 2019.

“It was a huge goodbye. It wasn’t only a goodbye to the team, it was a really big goodbye to our lifestyle,” Bejarano explained.

“I cried so much the day that they left.”

Bejarano said he barely had a social life after the Raiders departed. It was hard to find excuses to get people together once a week, or even once a month. The close ties between Bejarano and his hardcore Latino group started to unravel when their team bolted.

Back then, it felt like that sense of belonging was gone for good.

The exodus

Sports provide a valuable distraction from reality. A game can be the finishing line after another arduous week. In Oakland, where crime soared in 2023 and poverty is almost 2% higher than the national rate, following a team offered a welcome break from the struggles of day-to-day life.

But, bit by bit, Oaklanders have been denied those opportunities to escape.

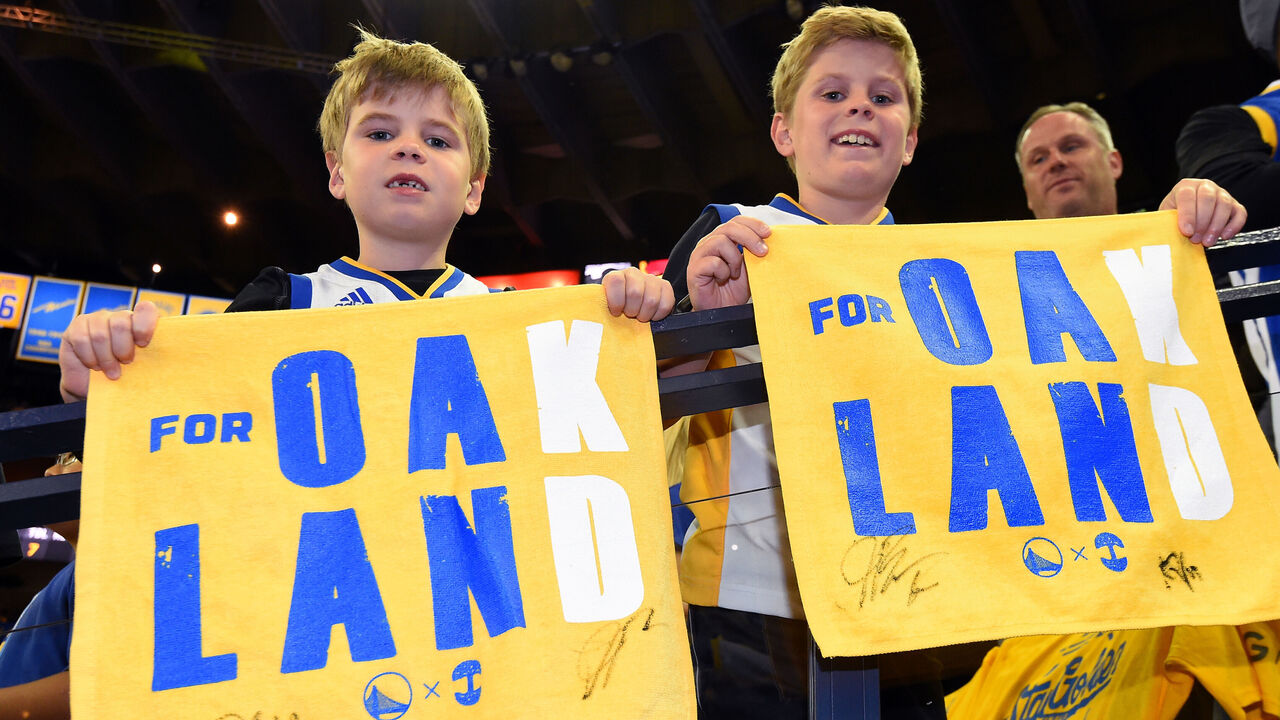

The Raiders kicked off in Las Vegas in 2020. San Francisco, Oakland’s glitzy neighbor, tempted the NBA’s Golden State Warriors across the bay the previous year, and is set to host the Bay Area’s new WNBA team beginning in 2025. MLB’s Oakland Athletics’ lease at the Coliseum expires in 2024 and the team doesn’t plan to stick around; its owners voted unanimously last November to approve the franchise’s long-touted move to Vegas.

Paul Brekke-Miesner, an Oakland sports historian, can’t recall another city losing three sports teams in such a short span.

“I think the biggest hurt of all is that rooting for your sports teams, it’s a community event,” Brekke-Miesner, 78, explained. “We have lots of different races and economic classes and cultures in Oakland. We’re one of the most diverse cities in America and all these diverse groups of people come together and root for the home team.”

Brekke-Miesner blames greed for teams leaving Oakland, and is particularly bothered by the Athletics’ ongoing departure. The acrimonious exit has contributed to a misconception about the city’s relationships with its teams. The A’s seemed to construct a narrative that blamed fans for dwindling attendance; a franchise with a .340 winning percentage over the past two seasons and that wanted taxpayers to cover significant costs relating to a proposed new stadium apparently wasn’t at fault.

“They’ve turned the script and they’ve blamed Oakland and Oakland fans for not supporting the teams, which is total bullshit,” Brekke-Miesner said. “Oakland has some of the most rabid fans of any city in America and we supported the teams.”

Investing in the community

Edreece Arghandiwal leads a fresh generation for sports in the city. He was born in Oakland to immigrants from Afghanistan and raised in the Bay Area. His family is infatuated with the area’s identity, drawing parallels between the diversity and resilience of Oaklanders and Afghans. But they mostly love the elements that belong exclusively to Oakland: the social awareness that led to movements like the Black Panther Party, its music and other art forms, its food, and, most of all, its sports.

“Oakland truly made these organizations what they were,” Arghandiwal said of the teams that turned their back on his city. “It was the people.”

As the co-founder of Oakland Roots and Oakland Soul Sports Club, a soccer organization that encompasses professional teams for both men and women, he’s building a brand that focuses on hometown pride and promotes the community.

The club supports non-profit organizations that use sports and arts to serve disadvantaged Oakland youth. The club’s youth academy is named Project 51O – a reference to Oakland’s area code, but with the letter “O” as an extra nod to the city – and has already created a pathway to first teams through its partnerships with local soccer programs. There are numerous tales of people buying Roots and Soul’s distinctive pro-Oakland merchandise, which is produced by local company Oaklandish, without knowing there’s professional soccer in town. Bay Area music entertains diverse crowds on matchdays while local vendors provide sustenance.

The club refuses to ask for public funding when Oakland has more pressing, non-sporting issues to address. So, Roots and Soul attracted 5,434 new owners to invest $3.17 million into the club between Sept. 13, 2023 and Nov. 1, 2023. Some of Oakland’s prestigious sporting alumni, like Marshawn Lynch and Jason Kidd, along with big-name musicians like rap star G-Eazy and Green Day frontman Billie Joe Armstrong, hold equity in the company. Last year’s influx of money, which was collected via a Wefunder page, is being used for general operations as the teams prepare to compete in the USL Championship and USL W League’s 2024 campaigns.

“It’s not just about what happens inside of the diamond or inside of the boundaries on the soccer pitch or a basketball court. It’s much larger than that when you invest in the community. People will invest back into you and represent you in ways that you wouldn’t have asked for,” Arghandiwal explained.

“We designed our identity to not exist without Oakland.”

The Oakland Ballers, a new baseball team, are appreciative of the relationship they’ve forged with the Roots and Soul. Two weeks after the A’s move from Oakland was green lighted, the Ballers – or B’s – announced they’ll begin their inaugural season in the independent Pioneer Baseball League in May.

“The Roots and the Soul are kind of like our Oakland sports big siblings,” B’s co-founder and CEO Paul Freedman told theScore. “They’ve been teaching us a lot and we admire and appreciate their mentorship. They’ve been wonderful for us.”

Another organization that’s leaned on the Roots and Soul is the Oakland Spiders, the only other active professional team in Oakland outside of its soccer teams and the departing A’s. The Spiders, an ultimate frisbee team, promote their product at Roots and Soul matches, and the soccer club’s helped them find field space and facilitated conversations with merchandise partners and sponsors.

“I respect the hell out of that. I think that’s a testament to the people that are in the organization. It’s a testament to their commitment, to their values,” Spiders president Jackson Stearns said, noting that such genuineness and generosity goes a long way in Oakland.

The Spiders are undertaking arguably the hardest job among their peers. Oakland has a long and proud association with baseball, and soccer is the world’s biggest sport, but the Spiders often have to educate people on their game before trying to sell it. Still, it may help that all the teams are flying under the same flag in this new era for the city.

“There’s a lot of shit being talked about what the Oakland fans are and a lot of what Oakland is as a city. If the Roots, the Soul, the Spiders, and the Ballers can be part of countering that bullshit messaging – (we’re) proud to do it and we will fight for it,” Freedman said.

Finding a new home

The buzz around the Roots and Soul eventually reached Bejarano.

“The moment we sat there, we realized how much of that Oakland pride was being brought into the stands,” the former Raiders superfan recalled of his first Roots experience, attended with a close friend.

The intimate party atmosphere was compelling. They had to be at the next match. Bejarano, a visual artist, started to create stickers featuring cartoon versions of the players and distributed the packs – named “Los Roots” – around the stands. But it was hard for Bejarano to commit to every home game while he “wasn’t fully there with money.”

That’s when a blend of luck and perseverance helped usher Bejarano into a world that “recreated everything” he and his friends thought they’d lost when the Raiders left for Vegas.

There was a promotion at an Easter-themed Roots match where two season tickets were hidden inside an egg. “We walk into the stadium and there are thousands and thousands and thousands of eggs everywhere. (In) bushes, on the booths, on the taco trucks, on benches, on the floor, everywhere,” Bejarano recalled.

Bejarano said he and his friend searched around the stadium three times before and during the game. They were pessimistic, and that feeling was compounded each time they saw groups of kids hurtling into bushes and diving under seats to find eggs. Eventually, they defeatedly slumped in their seats, until a staff member informed them the season tickets still hadn’t been found. They revived their search. And when they were about to give up for good, there it was, the magical golden egg, underneath a seat, ensuring they could attend matches for the rest of the season.

Soon, their support became more colorful. Bejarano and his friend, inspired by fans of their beloved Mexican club Chivas, wore luchador masks, brought flags and banners, and chanted while hanging over the railings. Over time, a Latin-forward contingent grew under the name “Los Roots.” Some of the supporters latched on to the group through Roots and Soul matches, but Bejarano believes there are around 30 who now keenly support Oakland’s soccer teams after passionately following the Raiders in the past.

The Roots and Soul’s move to another temporary home in Hayward (south of Oakland, in the East Bay) for the 2023 season brought the atmosphere even closer to what Bejarano loved from his days as an avid Raiders attendee. Open containers and music are allowed. Bejarano’s clan is basically doing what it did near the Coliseum – there are DJs, beers, and tacos – with one crucial exception: at these games, an owner will text him to check if his crew has everything it needs.

“It’s way more intimate. I tell all my friends all the time: we dedicated so much money and time and effort to the Raiders, yet the owner never knew who we were,” Bejarano said.

The Raiders moved to Vegas, but Bejarano and his friends moved their hearts to another city institution. It’s a different team, and a different sport, but they’re still supporting Oakland.