How the Celtics rose from the dead to give themselves a chance at history

The Celtics were dead and buried … until suddenly they weren’t.

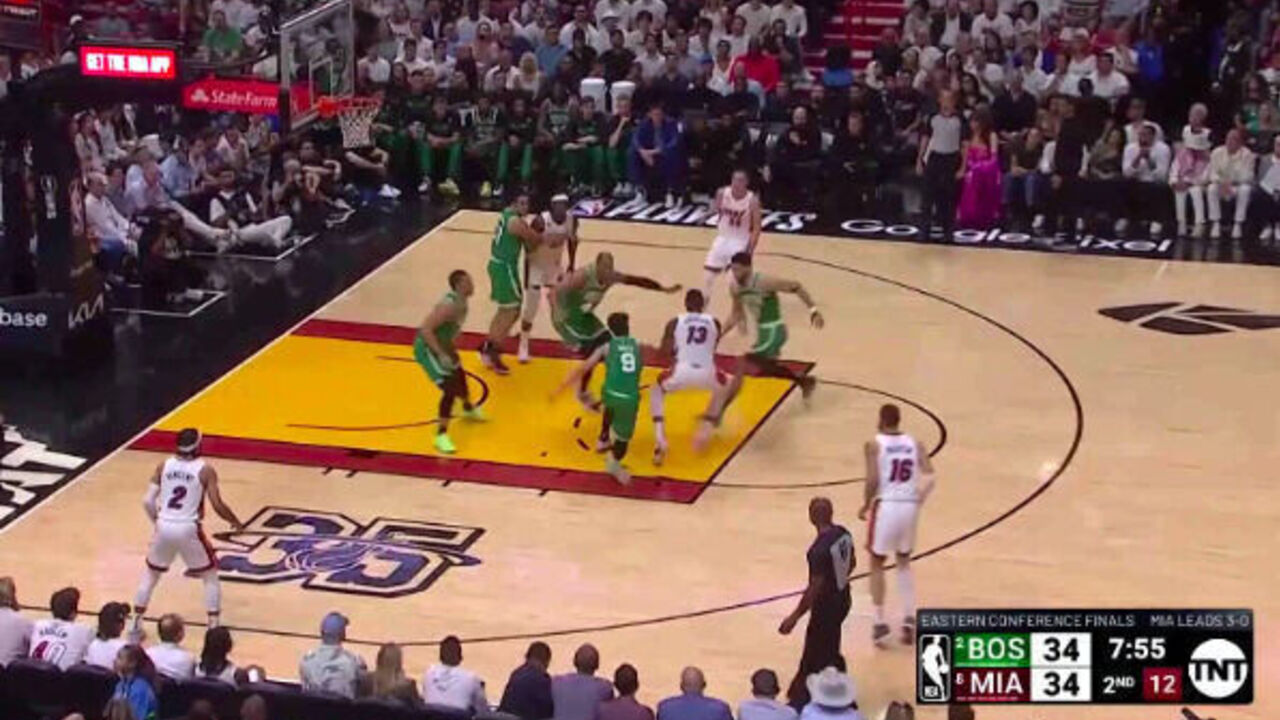

Trailing the Heat 3-0 in the Eastern Conference final, and down nine points in the third quarter of Game 4 in Miami, they pulled themselves out of the dirt. A mere 48 hours later, they were putting the finishing touches on a decisive Game 5 win, sending the series back to South Beach for a monumental Game 6. How exactly did we get here, and can Boston turn this cute comeback story into a historic one?

There’s an unavoidable “make-or-miss” element to this series – jump-shooting variance explains a lot of what’s transpired. Through three games, the Celtics were shooting 29.2% from deep while the Heat smoldered at 47.8%. Never mind that Boston was ostensibly creating better shots – more wide-open threes and significantly more threes off the catch – for what appeared to be (based on regular-season evidence, at least) a much stronger group of shooters.

In Games 4 and 5, the shotmaking pendulum swung: the Celtics shot 40.5% from 3-point range while the Heat cooled to 30.9%. Miami’s pull-up proficiency experienced a particularly big drop-off, falling from 44.7% to 22.2% on off-the-bounce threes. That tells a big part of the story of this turnaround, but as always, there’s more to it.

For one thing, the process by which a team generates its threes is important, and the Celtics improved that process over the past couple of games with crisp, rapid ball movement and snappy decision-making to beat the Heat’s ball pressure and stay a step ahead of their defensive rotations. Miami was unable to generate the same type of offensive flow. To wit: Boston averaged 17 wide-open threes in Games 4 and 5, up from 14.3 in the first three games of the series. Miami, conversely, averaged just six wide-open threes in its two losses as the Celtics tightened the screws defensively.

Let’s start by focusing on the Celtics’ offensive improvements.

The most obvious one, apart from getting more threes to fall, was that their ball movement was way more fluid. After averaging 254 passes and 44 potential assists in Games 1 through 3, they averaged 272 passes and 50 potential assists in Games 4 and 5, per NBA Advanced Stats. To a man, there was far less hesitation when it came to making decisions off the catch. Once an advantage was created, they stretched it and stretched it until the elastic snapped:

The Celtics also shot 75% at the rim in Games 4 and 5, largely by leveraging the 3-point threat and making a point of having their bigs slip to the rim. One interesting wrinkle was having those bigs slip out of off-ball screens, be they flare screens or wide pindowns for Jayson Tatum or Jaylen Brown – actions that tend to pull two defenders toward the shooting threat. When those slips weren’t creating cutting layups and dunks, they were working to create open threes by pulling in weak-side help:

The Celtics were also more intentional about getting into their offense quickly. They nearly doubled their transition frequency from the first three games of the series, and while a lot of that relates to forcing more turnovers (which we’ll get to in a bit), it also reflects their commitment to pushing the pace off of Miami’s misses. Attacking early, before the Heat had a chance to establish their shell or set up their zone or organize their back-line help, proved to be a pretty good way to open up shots at the rim:

Boston’s average offensive possession following a defensive rebound was 3.2 seconds faster than Miami’s over the last two games, according to Inpredictable.

Zooming out, the main reason the Celtics have been able to get back in the series is that they’ve picked all the low-hanging fruit. They came into this series as favorites because they have certain built-in matchup advantages, the biggest one being that the Heat have more exploitable defenders in their rotation. Sure, Jimmy Butler’s had plenty of success attacking All-Defensive second-teamer Derrick White in this series, and Miami as a whole has had success against Al Horford in drop, but that isn’t quite the same as Tatum going at Duncan Robinson, Max Strus, or Kevin Love.

Miami’s coverage of choice when one of those vulnerable defenders gets put in ball-screen action is either to hedge and recover or switch and double. The Celtics downloaded that and ultimately oriented their offense around targeting those pressure points with Tatum, getting two on the ball, and playing out of it.

Miami’s non-Bam Adebayo bigs (Love and Cody Zeller) are hedging against Tatum every time. He seems to prefer bringing those guys into ball-screen action in the middle of the floor so they can’t use the sideline as an extra defender and use their size to pin him there. With more room to operate, Tatum can beat those hedges with kicks to popping big men or even the odd crossover to split two defenders and take it to the rack himself. He’s more apt to run empty-side pick-and-rolls when attacking smalls like Strus and Robinson, and in those scenarios, he’s seeing a few more switch-doubles. His decision-making against all of those coverages has been on point, and his teammates have done a fantastic job capitalizing on the advantages he’s creating.

Tatum finished with 18 assists across Games 4 and 5, and that still vastly understates the totality of his playmaking impact. NBA Advanced Stats also credited him with six secondary assists (i.e. “hockey assists”) – plays in which he made the pass that directly set up the assist and basket that followed. If that doesn’t sound like a lot, bear in mind that those assists are attributed extremely judiciously, and no other player in the entirety of these conference finals has registered as many as Tatum did in the last two games alone.

Miami has turned to its zone a lot in an effort to hide those defenders and keep them on the floor for offensive purposes, but Boston has started to get a lot more comfortable against that coverage, too. You have to wonder if the Heat will finally pull the plug on the Love experience, at least in the starting lineup. There are already so many places for Tatum to attack, and giving him that automatic show-and-recover read for even 10-12 minutes a game feels like playing with fire.

Miami’s defensive approach contrasts that of the Celtics, who have mostly aimed to avoid putting two on the ball. They’re comfortable dropping back against most of the Heat’s pick-and-roll ball-handlers, even after getting torched by hot pull-up shooting in Games 1 through 3. There are exceptions – Boston’s bigs come up to the level against Strus and Robinson – but even in those scenarios, they’re aiming to recover to their original assignments and they trust their on-ball defenders to fight over the screen. (The rear-view pressure those on-ball defenders have been able to apply is a big part of the reason Boston suppressed Miami’s 3-point volume in the last couple games.)

Boston is also switching a ton, showing a willingness to do so on basically any action that doesn’t involve Horford. That includes continuing to give Butler the White matchup whenever he desires it, and trusting White (who’s fared better in that matchup as the series has gone on) to survive on an island.

Notably, the Celtics are also switching Robert Williams III out quite a bit. They’re typically reluctant to use him as a switch defender, not because he’s incapable but because he’s more valuable to them as a rim-protector lurking around the basket. But the Heat don’t offer him a natural hiding spot to roam off of (the way Philly did with P.J. Tucker, for instance), and they’ve looked pretty comfortable attacking him in drop coverage, so Boston decided to accept the tradeoff. Williams has rewarded them with some very strong switching defense over the past two games.

He’s made loud plays, including blocking two of Butler’s 3-point attempts. And there have been quieter ones, like this play in which he switched onto Butler and then Caleb Martin in quick succession, recovered to Martin after recognizing that no switch was needed on the ensuing action, and cracked back to snare a defensive rebound after Grant Williams leapt to his aid:

Williams III’s ability to hold his own against Butler is particularly vital because when Butler decides to get off the ball in those scenarios, Williams doesn’t necessarily have to respect him as a jump-shooter and can still serve as a helper at the rim.

Going back to one-big lineups was the right adjustment for the Celtics, especially considering the way it opened up their offense. But from a defensive perspective, Williams’ sturdiness when matched up against Miami’s perimeter threats could make it more viable to play him and Horford together in Game 6.

Just because the Celtics have actively avoided blitzing the pick-and-roll doesn’t mean they haven’t applied ball pressure. They’re just bringing most of that pressure at the second level of defense, with aggressive stunts and digs on drives and post-ups and short rolls. They forced 31 Heat turnovers in Games 4 and 5 while committing just 19 of their own, rewriting another chapter of the early-series script. They’ve especially keyed in on making Adebayo uncomfortable in the middle of the floor. He finished with 10 costly giveaways across the two games, and you can kind of see why:

So, does all this mean the Celtics will keep the momentum rolling and become the first team in NBA history to complete a comeback from 3-0 down? Not necessarily.

We probably shouldn’t expect the Celtics to continue dominating the possession battle; they forced the fifth-lowest rate of opponent turnovers during the regular season while Miami forced the second-highest. They’re still overly jumper-reliant, so even a mildly cold shooting night can sink them. And the Heat still have plenty of pressure points they can hit. Horford, in particular, has been vulnerable in ball-screen coverage, often trying so hard to take away both the ball-handler and the roller that he winds up taking away neither. Gabe Vincent has been a huge part of Miami’s success; his absence in Game 5 was glaring, and if he can return from an ankle sprain for Game 6, it could make a huge difference.

It may well turn out that all the Celtics earned themselves was a stay of execution. Their margin for error evaporated long ago, and the Heat have two cracks at getting one more collective shooting heater or one more volcanic Butler performance to seal the deal. Regardless, the last two games serve as a reminder of what Boston is capable of when the shots are falling, the ball is moving, and the game plan is clicking at both ends of the court.

The Celtics didn’t necessarily need a proof of concept after riding a nearly identical roster with very similar principles to the doorstep of a title last year. But in salvaging (at least momentarily) a potentially catastrophic conference finals, they’ve secured a measure of validation all the same. And in the process, they’ve given themselves a decent chance to make history.